| Citation: | Hui Wang, Qian Zhang, Yuankai Sun, Wenfeng Tan, Miaojia Zhang. AdipoR1 promotes pathogenic Th17 differentiation by regulating mitochondrial function through FUNDC1[J]. The Journal of Biomedical Research. DOI: 10.7555/JBR.38.20240244 |

Unproofed Manuscript: The manuscript has been professionally copyedited and typeset to confirm the JBR’s formatting, but still needs proofreading by the corresponding author to ensure accuracy and correct any potential errors introduced during the editing process. It will be replaced by the online publication version.

Adiponectin receptor 1 (Adipor1) deficiency has been shown to inhibit Th17 cell differentiation and reduce joint inflammation and bone erosion in antigen-induced arthritis (AIA) mice. Additional emerging evidence indicates that Th17 cells may differentiate into pathogenic (pTh17) and non-pathogenic (npTh17) cells, with the pTh17 cells playing a crucial role in numerous autoimmune and inflammatory conditions. In the current study, we found that Adipor1 deficiency inhibited pTh17 differentiation in vitro and that the deletion of Adipor1 in pTh17 cells reduced the mitochondrial function. RNA-sequencing (RNA-seq) demonstrated a significant increase in the expression levels of Fundc1, a gene related to mitochondrial function, in Adipor1-deficient CD4+ T cells. Interference with the Fundc1 expression in Adipor1-deficient CD4+ T cells partially mitigated the effect of Adipor1 deficiency on mitochondrial function and pTh17 differentiation. In conclusion, the current study demonstrated a novel role of AdipoR1 in regulating mitochondrial function via FUNDC1 to promote pTh17 cell differentiation, providing some insights into potential therapeutic targets for autoimmune and inflammatory diseases.

A subpopulation of CD4+ T cells, also called T helper 17 cells (Th17), expressed the retinoid-related orphan receptor gamma-t (RORγt) and produce cytokines, such as interleukin-17 (IL-17) and IL-22[1–2]. Various autoimmune diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis (RA), multiple sclerosis, inflammatory bowel disease and psoriasis, are associated with the Th17 responses[3]. Recent findings suggest that the Th17 cells are heterogeneous and may differentiate into two subpopulations based on their pathogenicity: pathogenic Th17 (pTh17) cells and non-pathogenic Th17 (npTh17) cells[4]. In vitro differentiation of both pTh17 and npTh17 cells occurs under various cytokine conditions[5]. The differentiation of pTh17 cells is driven by IL-6, IL-23, and IL-1β[6], while transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1) and IL-6 promote the differentiation of npTh17 cells[7–8]. Although both pTh17 and npTh17 cells share the Th17 markers, such as IL-17A and RORγt, they possess distinct genetic blueprints that dictate their roles in either promoting immune disorders or maintaining immune balance[5,9].

PTh17 cells are rich in pro-inflammatory cytokines such as granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) and interleukin 23 receptor (IL-23R), but lack immune regulatory components such as IL-10 and CD5 Molecule Like (CD5L). Conversely, npTh17 cells exhibit minimal levels of GM-CSF and IL-23R, while showing some elevated levels of IL-10 and CD5L, which support tissue stability[6–7,10–12]. PTh17 cells can also be distinguished from npTh17 cells by transcription factors (Stat4, Tbx21) [6]. RA patients have been found to have a higher percentage of pTh17 cells in some studies. These cells may generate a significant amount of inflammatory cytokines, exhibit resistance to apoptosis, and demonstrate a lack of responsiveness to treatment. Moreover, pTh17 cells are difficult to be suppressd by Treg cells[4,13].

Adiponectin, a cytokine released by adipose tissue, is crucial for immune response and metabolic processes. The functions of adiponectin are carried out through its interaction with its receptors[14]. One of our previous studies showed that adiponectin and adiponectin receptor 1 (AdipoR1) were highly expressed in RA synovial tissues[15]. Adiponectin encourages the transformation of naïve CD4+ T cells into Th17 cells, contributing to synovial membrane inflammation and bone erosion in RA patients[16]. Deficiency of Adipor1 inhibited Th17 cell differentiation and reduced joint inflammation and bone erosion in antigen-induced arthritis (AIA) mice[17], suggesting that AdipoR1 was involved in the inflammatory process of RA by regulating Th17 differentiation. However, whether AdipoR1 is involved in regulating pTh17 differentiation and the underlying molecular mechanisms remains unclear.

Mitochondria and mitochondrial membrane remodeling influence complex cell signaling events, including those regulating cell pluripotency, division, differentiation, aging, and apoptosis[18]. It has been shown that the electron transport chain complexes, the impairment of oxidative phosphorylation, and altered mitochondrial morphology all play key roles in the spectrum of pTh17 cell differentiation [19]; however, attenuated Th17 cell function might be related to genes involved in mitochondrial function that are expressed at lower levels[19–20].

FUN14 domain containing 1 (FUNDC1) is a novel mitochondrial membrane protein that acts as a receptor for hypoxia-induced mitochondrial autophagy[21]. FUNDC1-mediated mitochondrial autophagy selectively removes dysfunctional mitochondria, which in turn reduces damage to cells and tissues[22–23]. FUNDC1 also plays a crucial role in mitochondria-associated membranes (MAMs), the interface between mitochondria and the endoplasmic reticulum, which may promote the stabilization of MAMs, while also promoting endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ transfer to mitochondria and cytoplasm[24].

In the current study, we investigated the effects of knockout Adipor1 on pTh17 induced differentiation and mitochondrial function. Because FUNDC1 and mitochondrial function are closely related, we also explored the role of Adipor1 on pTh17 cell differentiation and mitochondrial function in the context of FUNDC1 expression.

As detailed in the reference[17], we created Adipor1fl/flCd4-Cre conditional knockout (CKO) mice. Cre-negative littermates are referred to as wild-type (WT) controls. Every creature belonged to the C57BL/6 genetic lineage. We only used male mice, aged between 6 and 8 weeks, and these mice were maintained in a germ-free setting. All animal experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Nanjing Medical University, Nanjing, Jiangsu, China (IACUC-2013090101).

In the Th17 differentiation experiments conducted in vitro, we extracted naïve CD4+ T cells (CD4+ CD62L+ T cells) from the spleen, and the single-cell suspensions were refined through negative selection with magnetic beads (Cat. #19765A, Stemcell, Vancouver, BC, Canada). We pretreated the 96-well plates with 50 μL phosphate buffer solution (PBS) containing 10 μg/mL anti-CD3e mAb (eBioscience, San Diego,CA, USA) and 3 μg/mL anti-CD28 mAb (eBioscience) at 4 ℃ for 16 h. We then added

We extracted total RNA by using Trizol (Accurate, Changsha, Hunan, China). Following the manufacturer's guidelines, the HiScript® Ⅱ Q RT SuperMix for qPCR (Vazyme, Nanjing, Jiangsu, China) was utilized to transform RNA into complementary deoxyribonucleic acid (cDNA). Quantitative PCR was conducted using ChamQ SYBR qPCR Master Mix (Vazyme) with the gene-specific primers. The sequences of primer pairs are listed in the Supplementary Table 1 (available online). Gene expression levels were standardized to Actb, and alterations in gene expression were determined using the 2−ΔΔCT method.

We lysed the harvested cells by using lysis buffer on ice for half an hour, followed by a 10-minute boiling period. Protein concentration was determined using the bicinchoninic acid assay (BCA) (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, Massachusetts, USA). Equal amounts of samples were analyzed using the SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. The separated proteins were subsequently transferred to PVDF membranes. The membranes were then treated with 5% skim milk to block nonspecific binding, followed by incubation with primary and secondary antibodies sequentially. The PVDF membranes underwent scanning, followed by protein expression analysis with a gel imaging system. The primary antibodies utilized included anti-β-actin (1∶

We performed surface staining by using anti-CD4 (BioLegend, San Diego, CA, USA) and anti-CD62L (BioLegend) for 30 min. For intracellular cytokine staining, the cells were exposed to 500 ng/mL phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) (Sigma-Aldrich, Burlington, Vermont, USA), 500 ng/mL ionomycin (Sigma-Aldrich), and 10 μg/mL brefeldin A (eBioscience) for five to six hours. Then the cells were treated with fixation/permeabilization buffer (eBioscience) in darkness at 4 ℃ for 50 min, followed by staining with specific antibodies such as anti-IL-17A (BioLegend), anti-IFN-γ (BioLegend), anti-RoRγt (BioLegend, San Diego, CA, USA), and anti-IL-10 (eBioscience). The absolute number of cells was calculated based on the percentage of each population.

Following standard protocols, we treated the cells with tetramethylrhodamine ethyl ester (TMRE) probes (Beyotime, Shanghai, China), Fluo-4 AM probes (Beyotime), and MitoSOX™ Red mitochondrial superoxide indicator (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) to measure the mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP), intracellular Ca2+ levels, and mitochondrial reactive oxygen species (mROS), respectively.

Cells were collected in flow tubes and treated with 1x TMRE and 5μm MitoSOX™ probes, according to standard protocols for the detection of MMP or mROS, respectively. The cell nuclei were restained using Hoechst (Beyotime, Shanghai, China). After washing with culture medium, the cell suspension was added on the slides, and the fluorescence intensity of the cells was examined by inverted fluorescence microscopy.

On the third day of naïve CD4+ T cell differentiation into pTh17 cells, we harvested the cells, which were centrifuged, and preserved in 0.1 mol/L PBS with 3% glutaraldehyde. Following sectioning and dual staining with uranium-lead, images were observed and recorded using a Carl Zeiss Gemini EM 10 CR electron microscope (Germany), and then were evaluated by an independent investigator who was unaware of the study details.

We used a Seahorse XF extracellular flux analyzer (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA) to measure oxygen consumption rate (OCR) in pTh17 cells. To immobilize the cells, 150,000 cells per well were plated on XF96 microplates pre-treated with poly-D-lysine (Sigma). Before conducting the assay, the cells were kept in XF medium (Seahorse Agilent) within a non-CO2 incubator for 20 min. The OCR was assessed using the Mito stress test kit (Agilent) by sequentially administering 1 µmol/L oligomycin, 1.5 µmol/L FCCP, and 0.5 µmol/L rotenone/antimycin A. The data were analyzed using Wave software.

We used PCR array plates to examine gene expression profiles linked to mitochondrial energy metabolism, following the manufacturer's instructions (Wcgene Biotech, Shanghai, China). The data were analyzed using Wegene Biotech software. Genes exhibiting a fold change exceeding 2 or falling below −2 were deemed biologically significant.

RNA was extracted from activated splenic CD4+ T cells derived from Adipor1 CKO mice and WT mice. cDNA sequencing libraries were generated and sequenced using the Illumina HiSeq platform, employing a 2 × 150 base pair paired-end sequencing approach. Differential gene expression was assessed by calculating fold changes in expression for each gene, determined by the ratio of the average fragments per kilobase of transcript per million mapped reads in the experimental group to that in the control group. The RNA sequencing (RNA-Seq) data have been deposited in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) under the accession number PRJNA624232.

Lentiviral vectors designed to express Fundc1-specific shRNA were constructed by GeneChem Co. Ltd. (Shanghai, China). A lentiviral vector containing only GFP was also constructed as a control for comparison. The shRNA-Fundc1 sequence was 5′-GAAGACACCACTGGTGGAATC-3′. Naïve CD4+ T cells were plated in 96-well plates at a density of 2 × 105 cells per 200 μL and activated with anti-CD3e mAb and anti-CD28 mAb for 24 h. Lentiviral vectors were then added to the 96-well plates at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 50. The medium was refreshed 24 h post-transfection. The transfection efficiency was evaluated by observing the cells through a fluorescence microscope. Furthermore, the efficiency of transfection was measured using qRT-PCR analysis.

We performed statistical analyses by using GraphPad Prism version 9.0.0 as well as one-way ANOVA and Student's t-tests. Significance was determined for P-values less than 0.05.

Initially, we used magnetic beads to sort naïve CD4+ T cells from the spleens of WT mice (Supplementary Fig. 1A, available online). After inducing differentiation of naïve CD4+ T cells into pTh17 and npTh17 cells for 72 h, we successfully generated CD4+IL-17A+ Th17 cells in both groups without statistically significant difference (Supplementary Fig. 1B, available online). Flow cytometry showed a minimal IL-10 protein expression in the pTh17 group, while the npTh17 group exhibited a significant increase in IL-10 protein levels (Supplementary Fig. 1C, available online). The qRT-PCR results showed an increase in Csf2 and Il23r expression levels, but a decrease in Il10 and Cd5l expression levels in the pTh17 cells, compared with those of the npTh17 cells (Supplementary Fig. 1D, available online). We also examined the expression levels of other genes that control the production of IL-10, including Ikzf3, Ahr and Maf, and found a significant difference in the expression levels of the gene Ikzf3 between the groups (Supplementary Fig. 1D). The results indicated that pTh17 and npTh17 exhibited different inflammatory properties, which was consistent with the literature [6-7, 10-12], suggesting that our induced differentiation system was successful.

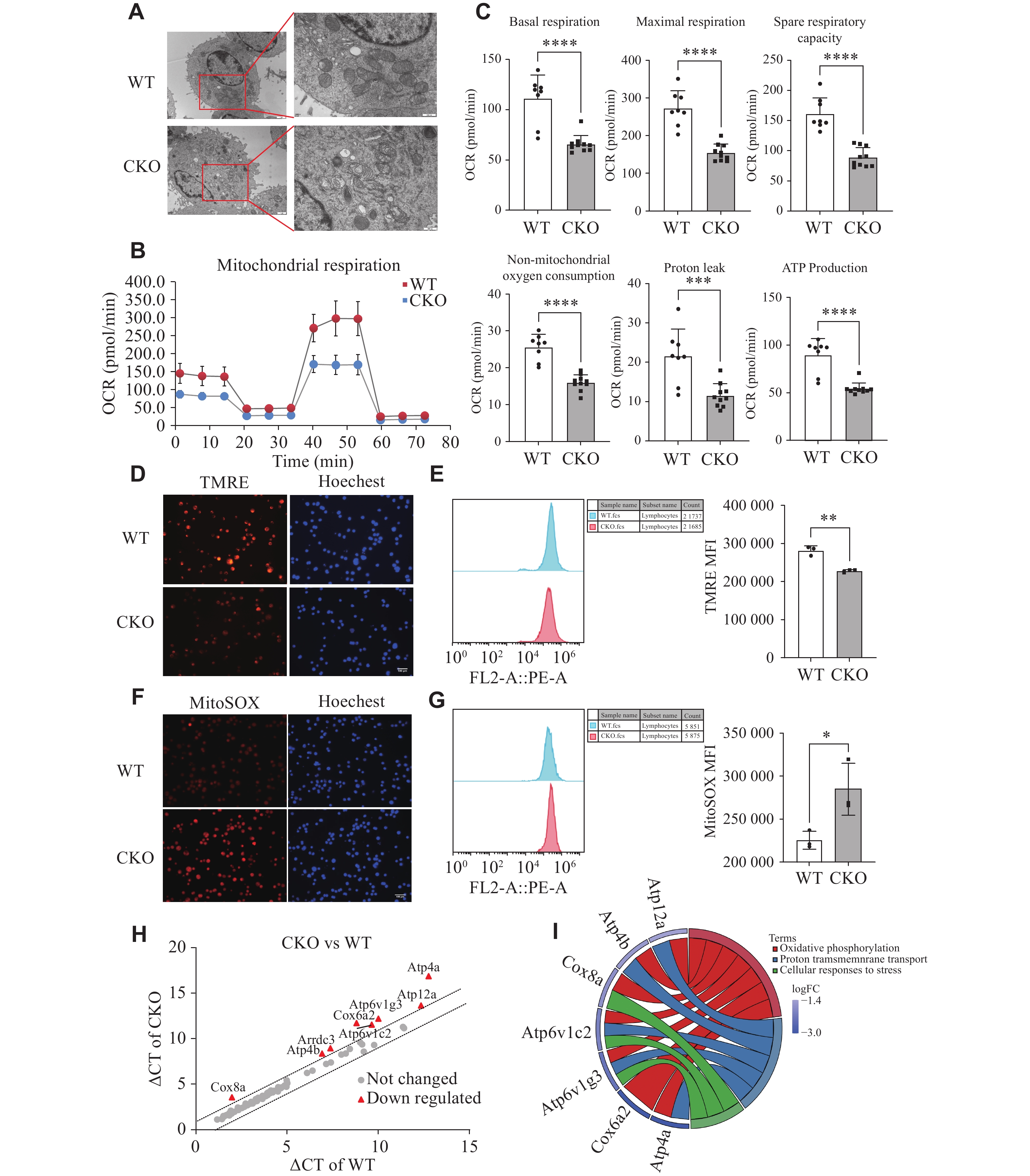

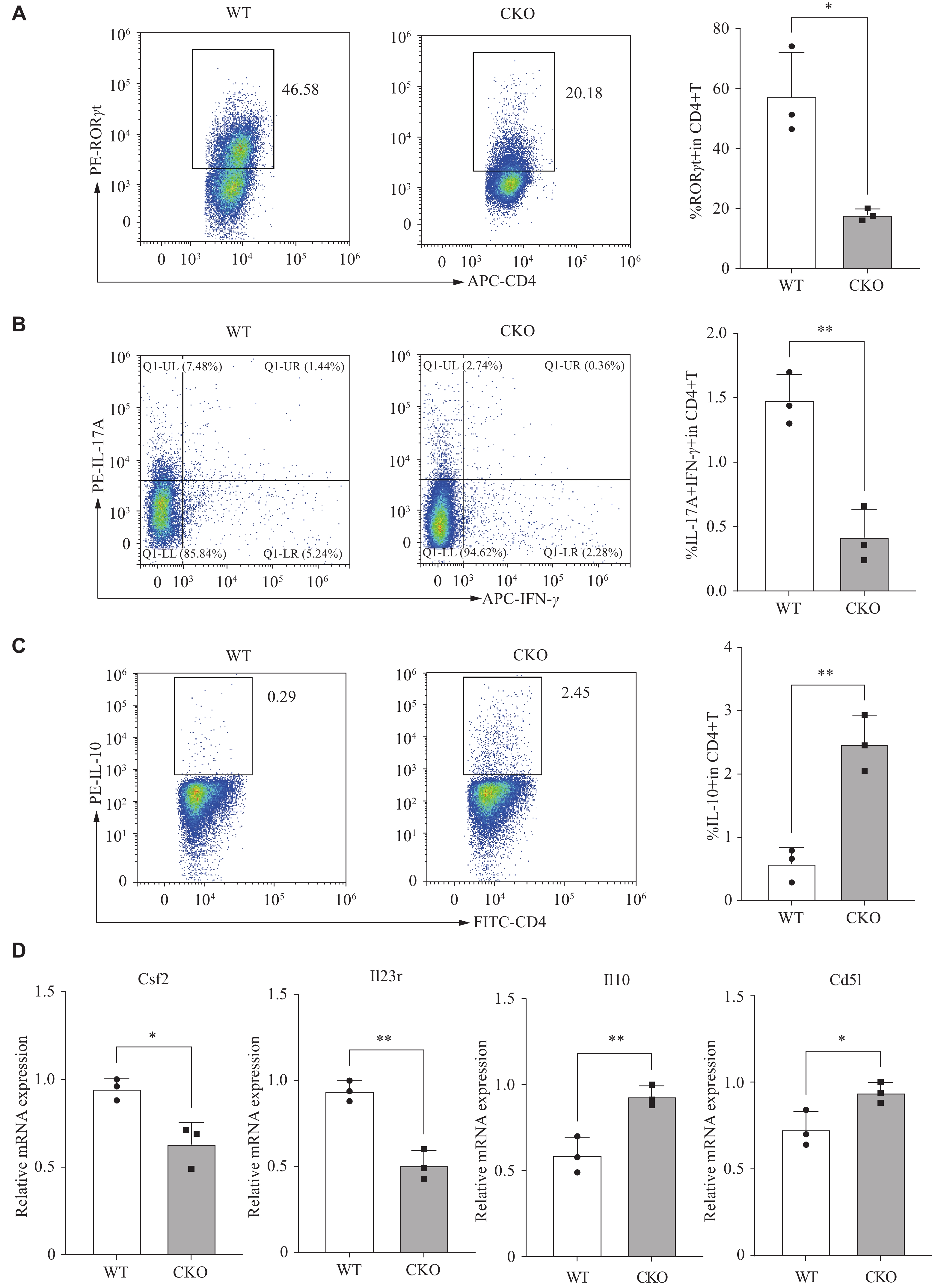

Subsequently, the spleen-derived naïve CD4+ T cells from both Adipor1 CKO and WT mice were induced to differentiate into pTh17 cells for 72 h. Given that pTh17 cells possess the signature of Th17 cells, we initially examined the expression of RORγt, a transcription factor characteristic of these cells. A significant decrease in CD4+RORγt+ T cells was observed in the Adipor1 CKO group, compared with that in the WT group (Fig. 1A). Because Th17 cells are pathogenic when TNF-α, IFN-γ, and GM-CSF are produced simultaneously, along with IL-17A[25], we investigated whether AdipoR1 modulated the differentiation of pTh17 (IL-17A+IFN-γ+) cells. The results showed that the Adipor1 knockout significantly reduced the proportion of pTh17 cells (Fig. 1B). We also examined the characteristic genes associated with pTh17 and npTh17 cells. Flow cytometry showed that IL-10 protein levels were significantly increased in pTh17 cells from the Adipor1 CKO group (Fig. 1C). The qRT-PCR revealed that pTh17 cells in the Adipor1 CKO group had lower expression levels of the pro-inflammatory molecules Csf2 and Il23r, but higher expression levels of Il10 and Cd5l than that of the WT group (Fig. 1D). These results suggested that the knockout of Adipor1 inhibited the pTh17 differentiation.

Considering that the mitochondrial shape and cristae architecture influence their functions, we initially employed transmission electron microscopy to observe the changes in mitochondrial morphology of pTh17 cells. We found that the mitochondria in pTh17 cells of the Adipor1 CKO group appeared light in color, with pronounced vacuolization and blurred cristae, compared with the WT group (Fig. 2A).

We assessed mitochondrial respiration in pTh17 cells to investigate the effect of AdipoR1 on their mitochondrial function. The mitochondrial respiration, indicated by oxygen consumption rates, was significantly lower in pTh17 cells from the Adipor1 CKO group than in those from the WT group (Fig. 2B and 2C). MMP was measured using the TMRE probe, revealing that the knockout of Adipor1 significantly reduced the MMP of pTh17 cells (Fig. 2D and 2E). In addition to ATP production, another crucial function of mitochondria is the generation of mROS. We observed that the knockout of Adipor1 induced mROS production in pTh17 cells (Fig. 2F and 2G).

Furthermore, PCR arrays were used to detect genes involved in mitochondrial energy metabolism. The results showed that the mRNA levels of Atp4a, Cox6a2, Atp6v1g3, Atp6v1c2, Cox8a, Arrdc3, Atp4b and Atp12a were significantly reduced in pTh17 cells from the Adipor1 CKO group relative to those of the WT group (Fig. 2H). These differential genes mainly affected proton transmembrane transport and oxidative phosphorylation levels (Fig. 2I). All these results indicated that the knockout of Adipor1 might inhibit the mitochondrial functions of pTh17 cells.

We examined gene expression profiles of the activated CD4+ T cells in WT and Adipor1 CKO mice using RNA sequencing, and identified 95 upregulated and 551 downregulated genes in the Adipor1 CKO group, with Fundc1 being the most significantly altered gene (P = 1.56E−09, log2FC = 1.54) (Fig. 3A and 3B), which was further validated by Western blotting and qRT-PCR in pTh17 cells, and both protein and mRNA expression levels of FUNDC1 were found to be elevated in pTh17 cells with Adipor1 knockout (Fig. 3C and 3D), which was consistent with the RNA-seq results.

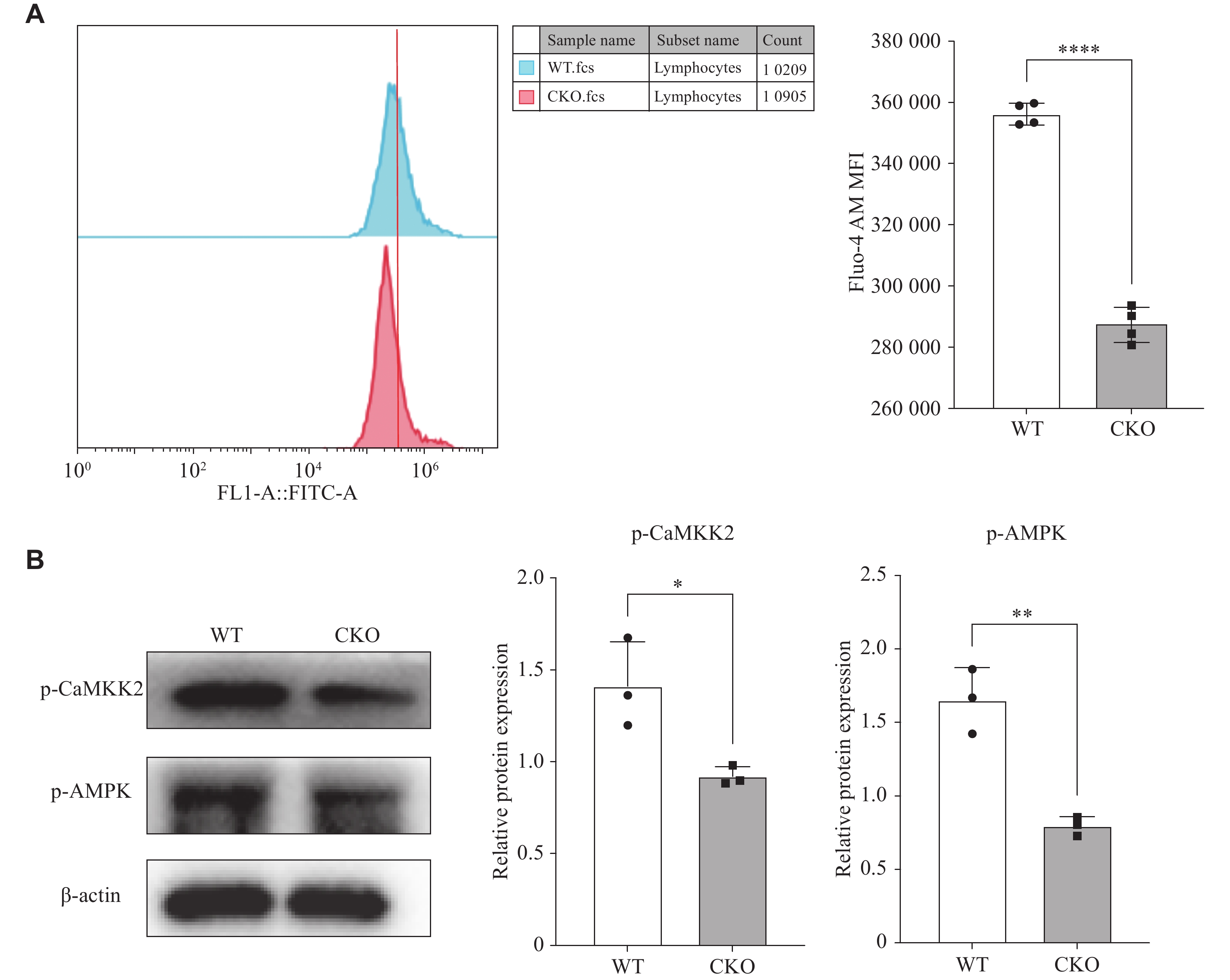

Adiponectin was reported to increase intracellular Ca2+ concentration by inducing extracellular Ca2+ influx via AdipoR1, and this intracellular Ca2+ accumulation activated the CaMKK2/AMPK signaling cascade, with FUNDC1 identified as a downstream target of AMPK[20–22]. Therefore, we used Fluo-4 AM calcium ion fluorescent probe to determine the intracellular Ca2+ concentration, and found that the intracellular calcium ion content in pTh17 cells with Adipor1 knockout was significantly reduced, compared with the WT group (Fig. 4A). Additionally, Western blotting results showed that the phosphorylation levels of CaMKK2 and its downstream gene AMPK were lower in Adipor1-deficient pTh17 cells than the WT group (Fig. 4B). These results suggest that AdipoR1 may inhibit FUNDC1 expression by activating AMPK phosphorylation through the regulation of transient calcium influx.

To test whether AdipoR1 regulated pTh17 differentiation through FUNDC1, we constructed lentiviruses to interfere with FUNDC1 expression and infected activated naïve CD4+ T cells (Fig. 5A). The mRNA expression of Fundc1 was reduced by approximately 50% after infection with lentivirus (Fig. 5B). We found that inhibition of FUNDC1 expression under pTh17 cell-induced differentiation conditions not only reversed the inhibitory effects of Adipor1 deficiency on the expression of IL-17A, RORγt (Fig. 5C and 5D); it also partially reversed the inhibitory effects of cytokines and transcription factors associated with pTh17 cells (Fig. 5E). To further clarify the effect of interfering with Fundc1 on the mitochondrial function of pTh17 cells, we examined the MMP and mROS levels, and found that inhibiting Fundc1 significantly ameliorated the decrease in MMP and the accumulation of mROS in the Adipor1 CKO group (Fig. 5F and 5G). These findings indicate that AdipoR1 may affect mitochondrial function via FUNDC1 to enhance the differentiation of pTh17 cells.

PTh17 cells are thought to play a critical role in the development of rheumatoid arthritis that may be diagnosed, treated, and prognosed by targeting pTh17 cells or their associated molecules[26]. Here, we showed that the knockout of Adipor1 resulted in a significant reduction in the proportion of naïve CD4+ T cells differentiating into pTh17 cells. We also found that the loss of Adipor1 in pTh17 cells resulted in gene expression profiles similar to those observed in WT npTh17 cells. The results indicate that AdipoR1 is essential for the development and activity of pTh17 cells, and its absence skews these cells towards an npTh17-like phenotype. This highlights the potential of targeting AdipoR1 to modulate pTh17 cell activity in treatment strategies for rheumatoid arthritis.

The effect of adiponectin and its receptors on Th17 cell differentiation is currently controversial, possibly because adiponectin exists in the plasma as multimeric forms, including trimer, hexamer, high molecular weight oligomer, and a free globular structural domain generated by the proteolytic cleavage of the C-terminus, leading to different biological functions[27–28]. Adiponectin exerts its biological function by acting on its receptors, AdipoR1 and AdipoR2. AdipoR1 is highly expressed in skeletal muscle, whereas AdipoR2 is highly expressed in the liver and the kidney. Both receptors belong to the G protein-coupled receptor family, but differ in amino acid sequence, resulting in differences in affinity and binding specificity for adiponectin. It has been reported that KS23, a novel peptide derived from adiponectin, downregulates the proportion of Th17 cells during experimental autoimmune uveitis[29]. This seems to contradict our findings, but it is not clear whether KS23 acts directly on AdipoR1. It has also been reported that AdipoRon, an agonist of AdipoR1 and AdipoR2, inhibits Th17 cell differentiation. However, the effect of AdipoRon on Th17 cell differentiation was abolished by AdipoR2 blockers but not by AdipoR1 blockers[30]. Therefore, we tested the effect of Adipor1 deficiency on AdipoR2 expression, and found that there was a tendency for AdipoR2 to be reduced at the protein and nucleic acid levels, but there was no statistically significant difference (Supplementary Fig. 2, available online). Several studies are consistent with our findings[28]. Thus, these receptors play different roles under different physiological and pathological conditions.

In addition, we found that Adipor1-deficient pTh17 cells had abnormal mitochondrial morphology and attenuated mitochondrial function. To investigate the potential mechanisms by which AdipoR1 regulates pTh17 cell differentiation. We analyzed the RNA-seq gene expression profiles of the activated CD4+ T cells from both Adipor1 CKO and WT mice. This analysis identified Fundc1 as a significantly differentially expressed gene, which we validated in pTh17 cells with Adipor1 knockout. FUNDC1, a mammalian mitophagy receptor, interacts with and recruits microtubule-associated protein 1A/1B-light chain 3 (LC3) to mitochondria for mitophagy[21]. In contrast, in mammals, phosphorylated FUNDC1 inhibits binding to LC3, thereby blocking subsequent mitophagy[31–32]. FUNDC1 is also a novel MAM protein that is enriched at the MAM. In cardiomyocytes from a mouse model of diabetes, FUNDC1 was highly expressed, and it might promote MAM formation by interacting with IP3R2, which led to an increase in the expression of Ca2+ and Fis1 in the mitochondria, resulting in mitochondrial dysfunction, which in turn impaired myocardial structure and function[33]. These findings highlight the crucial role of FUNDC1 in regulating mitochondrial function. Therefore, we hypothesized that Adipor1 knockout might inhibit pTh17 cell differentiation by affecting mitochondrial function through the upregulation of FUNDC1 expression.

AdipoR1, as a membrane protein, regulates FUNDC1 expression by inducing extracellular Ca2+ influx, which increases intracellular Ca2+ concentrations[34]. This intracellular Ca2+ accumulation activates the CaMKK2/AMPK signaling cascade[34–35]. Specific disruption of AdipoR1 suppresses adiponectin-mediated increases in intracellular Ca2+ concentration and reduces CaMKK and AMPK activation[34]. Research has shown that the inhibition of FUNDC1 through AMPK activation is an effective approach to treating diabetic cardiomyopathy, confirming FUNDC1 as a downstream target of AMPK[33]. We detected intracellular Ca2+ levels by flow cytometry and analyzed CaMKK2 and AMPK phosphorylation levels by Western blotting. Our results suggest that AdipoR1 might inhibit FUNDC1 expression by activating AMPK phosphorylation through transient calcium influx.

To investigate further, we constructed lentiviruses to interfere with FUNDC1 expression and observed whether the effects of Adipor1 knockout on mitochondrial function and pTh17 differentiation could be reversed. The results showed that interfering with FUNDC1 partially restored mitochondrial function and the differentiation capacity of Adipor1-deficient pTh17 cells. However, the precise mechanisms by which FUNDC1 affects mitochondrial function require further experimental validation.

In summary, this research is the first to discover and demonstrate that knockout of Adipor1 activates FUNDC1 expression, and it is also the first to report that FUNDC1 inhibits pTh17 differentiation by affecting mitochondrial function. Our data lay the foundation for the molecular mechanisms by which AdipoR1 regulates the pTh17 pathway to affect rheumatoid arthritis as well as other autoimmune and inflammatory diseases mediated by pTh17. These findings offer a conceptual framework and empirical support for discovering novel treatment targets for these diseases.

This research received funding from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No.82071827) and the Jiangsu Province Natural Science Foundation (Grant No.BK20210963).

We acknowledge and appreciate Prof. Fang Wang and Prof. Meijuan Zou for their experimental technical support.

CLC number: R392.12, Document code: A

The authors reported no conflict of interests.

| [1] |

Langrish CL, Chen Y, Blumenschein WM, et al. IL-23 drives a pathogenic T cell population that induces autoimmune inflammation[J]. J Exp Med, 2005, 201(2): 233–240. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041257

|

| [2] |

Zhou L, Ivanov II, Spolski R, et al. IL-6 programs TH-17 cell differentiation by promoting sequential engagement of the IL-21 and IL-23 pathways[J]. Nat Immunol, 2007, 8(9): 967–974. doi: 10.1038/ni1488

|

| [3] |

Wu B, Wan Y. Molecular control of pathogenic Th17 cells in autoimmune diseases[J]. Int Immunopharmacol, 2020, 80: 106187. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2020.106187

|

| [4] |

Lin J, Tang J, Lin J, et al. YY1 regulation by miR-124–3p promotes Th17 cell pathogenicity through interaction with T-bet in rheumatoid arthritis[J]. JCI Insight, 2021, 6(22): e149985. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.149985

|

| [5] |

Stockinger B, Omenetti S. The dichotomous nature of T helper 17 cells[J]. Nat Rev Immunol, 2017, 17(9): 535–544. doi: 10.1038/nri.2017.50

|

| [6] |

Lee Y, Awasthi A, Yosef N, et al. Induction and molecular signature of pathogenic TH17 cells[J]. Nat Immunol, 2012, 13(10): 991–999. doi: 10.1038/ni.2416

|

| [7] |

McGeachy MJ, Bak-Jensen KS, Chen Y, et al. TGF-β and IL-6 drive the production of IL-17 and IL-10 by T cells and restrain TH-17 cell-mediated pathology[J]. Nat Immunol, 2007, 8(12): 1390–1397. doi: 10.1038/ni1539

|

| [8] |

Veldhoen M, Hocking RJ, Atkins CJ, et al. TGFβ in the context of an inflammatory cytokine milieu supports de novo differentiation of IL-17-producing T cells[J]. Immunity, 2006, 24(2): 179–189. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.01.001

|

| [9] |

Ghoreschi K, Laurence A, Yang XP, et al. T helper 17 cell heterogeneity and pathogenicity in autoimmune disease[J]. Trends Immunol, 2011, 32(9): 395–401. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2011.06.007

|

| [10] |

Gaublomme JT, Yosef N, Lee Y, et al. Single-cell genomics unveils critical regulators of Th17 cell pathogenicity[J]. Cell, 2015, 163(6): 1400–1412. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.11.009

|

| [11] |

Omenetti S, Bussi C, Metidji A, et al. The intestine harbors functionally distinct homeostatic tissue-resident and inflammatory Th17 cells[J]. Immunity, 2019, 51(1): 77–89. e6. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2019.05.004

|

| [12] |

Wang C, Yosef N, Gaublomme J, et al. CD5L/AIM regulates lipid biosynthesis and restrains Th17 cell pathogenicity[J]. Cell, 2015, 163(6): 1413–1427. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.10.068

|

| [13] |

Toghi M, Bitarafan S, Ghafouri-Fard S. Pathogenic Th17 cells in autoimmunity with regard to rheumatoid arthritis[J]. Pathol Res Pract, 2023, 250: 154818. doi: 10.1016/j.prp.2023.154818

|

| [14] |

Khoramipour K, Chamari K, Hekmatikar AA, et al. Adiponectin: structure, physiological functions, role in diseases, and effects of nutrition[J]. Nutrients, 2021, 13(4): 1180. doi: 10.3390/nu13041180

|

| [15] |

Tan W, Wang F, Zhang M, et al. High adiponectin and adiponectin receptor 1 expression in synovial fluids and synovial tissues of patients with rheumatoid arthritis[J]. Semin Arthritis Rheum, 2009, 38(6): 420–427. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2008.01.017

|

| [16] |

Sun X, Feng X, Tan W, et al. Adiponectin exacerbates collagen-induced arthritis via enhancing Th17 response and prompting RANKL expression[J]. Sci Rep, 2015, 5: 11296. doi: 10.1038/srep11296

|

| [17] |

Zhang Q, Wang L, Jiang J, et al. Critical role of adipor1 in regulating Th17 cell differentiation through modulation of HIF-1α-dependent glycolysis[J]. Front Immunol, 2020, 11: 2040. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.02040

|

| [18] |

Giacomello M, Pyakurel A, Glytsou C, et al. The cell biology of mitochondrial membrane dynamics[J]. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol, 2020, 21(4): 204–224. doi: 10.1038/s41580-020-0210-7

|

| [19] |

Kaufmann U, Kahlfuss S, Yang J, et al. Calcium signaling controls pathogenic Th17 cell-mediated inflammation by regulating mitochondrial function[J]. Cell Metab, 2019, 29(5): 1104–1118. e6. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2019.01.019

|

| [20] |

Shin B, Benavides GA, Geng J, et al. Mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation regulates the fate decision between pathogenic Th17 and regulatory T cells[J]. Cell Rep, 2020, 30(6): 1898–1909. e4. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2020.01.022

|

| [21] |

Chen M, Chen Z, Wang Y, et al. Mitophagy receptor FUNDC1 regulates mitochondrial dynamics and mitophagy[J]. Autophagy, 2016, 12(4): 689–702. doi: 10.1080/15548627.2016.1151580

|

| [22] |

Cai C, Guo Z, Chang X, et al. Empagliflozin attenuates cardiac microvascular ischemia/reperfusion through activating the AMPKα1/ULK1/FUNDC1/mitophagy pathway[J]. Redox Biol, 2022, 52: 102288. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2022.102288

|

| [23] |

Zhou H, Li D, Zhu P, et al. Melatonin suppresses platelet activation and function against cardiac ischemia/reperfusion injury via PPARγ/FUNDC1/mitophagy pathways[J]. J Pineal Res, 2017, 63(4): e12438. doi: 10.1111/jpi.12438

|

| [24] |

Wu S, Lu Q, Wang Q, et al. Binding of FUN14 domain containing 1 with inositol 1, 4, 5-trisphosphate receptor in mitochondria-associated endoplasmic reticulum membranes maintains mitochondrial dynamics and function in hearts in vivo[J]. Circulation, 2017, 136(23): 2248–2266. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.030235

|

| [25] |

Lee Y, Awasthi A, Yosef N, et al. Induction and molecular signature of pathogenic TH17 cells[J]. Nat Immunol, 2012, 13(10): 991–999.

|

| [26] |

Mazzoni A, Maggi L, Liotta F, et al. Biological and clinical significance of T helper 17 cell plasticity[J]. Immunology, 2019, 158(4): 287–295. doi: 10.1111/imm.13124

|

| [27] |

Zhang K, Guo Y, Ge Z, et al. Adiponectin suppresses T helper 17 cell differentiation and limits autoimmune CNS inflammation via the SIRT1/PPARγ/RORγt pathway[J]. Mol Neurobiol, 2017, 54(7): 4908–4920. doi: 10.1007/s12035-016-0036-7

|

| [28] |

Jung MY, Kim HS, Hong HJ, et al. Adiponectin induces dendritic cell activation via PLCγ/JNK/NF-κB pathways, leading to Th1 and Th17 polarization[J]. J Immunol, 2012, 188(6): 2592–2601. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1102588

|

| [29] |

Niu T, Cheng L, Wang H, et al. KS23, a novel peptide derived from adiponectin, inhibits retinal inflammation and downregulates the proportions of Th1 and Th17 cells during experimental autoimmune uveitis[J]. J Neuroinflammation, 2019, 16(1): 278. doi: 10.1186/s12974-019-1686-y

|

| [30] |

Murayama MA, Chi HH, Matsuoka M, et al. The CTRP3-AdipoR2 axis regulates the development of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis by suppressing Th17 cell differentiation[J]. Front Immunol, 2021, 12: 607346. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.607346

|

| [31] |

Liu L, Feng D, Chen G, et al. Mitochondrial outer-membrane protein FUNDC1 mediates hypoxia-induced mitophagy in mammalian cells[J]. Nat Cell Biol, 2012, 14(2): 177–185. doi: 10.1038/ncb2422

|

| [32] |

Chen G, Han Z, Feng D, et al. A regulatory signaling loop comprising the PGAM5 phosphatase and CK2 controls receptor-mediated mitophagy[J]. Mol Cell, 2014, 54(3): 362–377. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.02.034

|

| [33] |

Wu S, Lu Q, Ding Y, et al. Hyperglycemia-driven inhibition of AMP-activated protein kinase α2 induces diabetic cardiomyopathy by promoting mitochondria-associated endoplasmic reticulum membranes in vivo[J]. Circulation, 2019, 139(16): 1913–1936. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.033552

|

| [34] |

Iwabu M, Yamauchi T, Okada-Iwabu M, et al. Adiponectin and AdipoR1 regulate PGC-1α and mitochondria by Ca2+ and AMPK/SIRT1[J]. Nature, 2010, 464(7293): 1313–1319. doi: 10.1038/nature08991

|

| [35] |

Kanno Y, Ishisaki A, Kawashita E, et al. uPA attenuated LPS-induced inflammatory osteoclastogenesis through the plasmin/PAR-1/Ca2+/CaMKK/AMPK axis[J]. Int J Biol Sci, 2016, 12(1): 63–71. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.12690

|

| [1] | Chen Li, Kerui Wang, Xingfeng Mao, Xiuxiu Liu, Yingmei Lu. Upregulated inwardly rectifying K+ current-mediated hypoactivity of parvalbumin interneuron underlies autism-like deficits in Bod1-deficient mice[J]. The Journal of Biomedical Research. DOI: 10.7555/JBR.38.20240394 |

| [2] | Yue Xiao, Yue Peng, Chi Zhang, Wei Liu, Kehan Wang, Jing Li. hucMSC-derived exosomes protect ovarian reserve and restore ovarian function in cisplatin treated mice[J]. The Journal of Biomedical Research, 2023, 37(5): 382-393. DOI: 10.7555/JBR.36.20220166 |

| [3] | Hongyan Li, Zhiyou Cai. SIRT3 regulates mitochondrial biogenesis in aging-related diseases[J]. The Journal of Biomedical Research, 2023, 37(2): 77-88. DOI: 10.7555/JBR.36.20220078 |

| [4] | Grapentine Sophie, Bakovic Marica. Significance of bilayer-forming phospholipids for skeletal muscle insulin sensitivity and mitochondrial function[J]. The Journal of Biomedical Research, 2020, 34(1): 1-13. DOI: 10.7555/JBR.33.20180104 |

| [5] | Kaibo Lin, Shikun Zhang, Jieli Chen, Ding Yang, Mengyi Zhu, Eugene Yujun Xu. Generation and functional characterization of a conditional Pumilio2 null allele[J]. The Journal of Biomedical Research, 2018, 32(6): 434-441. DOI: 10.7555/JBR.32.20170117 |

| [6] | Huanqiang Wang, Congying Yang, Siyuan Wang, Tian Wang, Jingling Han, Kai Wei, Fucun Liu, Jida Xu, Xianzhen Peng, Jianming Wang. Cell-free plasma hypermethylated CASZ1, CDH13 and ING2 are promising biomarkers of esophageal cancer[J]. The Journal of Biomedical Research, 2018, 32(6): 424-433. DOI: 10.7555/JBR.32.20170065 |

| [7] | Guilaine Boyce, Emily Button, Sonja Soo, Cheryl Wellington,. The pleiotropic vasoprotective functions of high density lipoproteins (HDL)[J]. The Journal of Biomedical Research, 2018, 32(3): 164-182. DOI: 10.7555/JBR.31.20160103 |

| [8] | Bing Zhang, Ling Ni, Fangfang Wang, Weiping Li, Xin Zhang, Xiaohua Gu, Zuzana Nedelska, Fei Chen, Kun Wang, Bin Zhu, Renyuan Liu, Jun Xu, Jinfan Wang. Effective doctor-patient communication skills training optimizes functional organization of intrinsic brain architecture: a restingstate functional MRI study[J]. The Journal of Biomedical Research, 2017, 31(6): 486-493. DOI: 10.7555/JBR.31.20160135 |

| [9] | Wenhua Xu, Mingfang Li, Minglong Chen, Bing Yang, Daowu Wang, Xiangqing Kong, Hongwu Chen, Weizhu Ju, Kai Gu, Kejiang Cao, Hailei Liu, Qi Jiang, Jiaojiao Shi, Yan Cui, Hong Wang. Effect of burden and origin sites of premature ventricular contractions on left ventricular function by 7-day Holter monitor[J]. The Journal of Biomedical Research, 2015, 29(6): 465-474. DOI: 10.7555/JBR.29.20150032 |

| [10] | Tiejun Zou, Xiang Liu, Shangshu Ding, Junping Xing. Evaluation of sperm mitochondrial function using rh123 /PI dual fluorescent staining in asthenospermia and oligoasthenozoospermia[J]. The Journal of Biomedical Research, 2010, 24(5): 404-410. DOI: 10.1016/S1674-8301(10)60054-1 |