| Citation: | Xiang Wang, Xuan Wang, Mengsheng Zhao, Lijuan Lin, Yi Li, Ning Xie, Yanru Wang, Aoxuan Wang, Xiaowen Xu, Can Ju, Qiuyuan Chen, Jiajin Chen, Ruili Hou, Zhongwen Zhang, David C. Christiani, Feng Chen, Yongyue Wei, Ruyang Zhang. Bidirectional Mendelian randomization and mediation analysis of million-scale data reveal causal relationships between thyroid-related phenotypes, smoking, and lung cancer[J]. The Journal of Biomedical Research. DOI: 10.7555/JBR.38.20240421 |

Unproofed Manuscript: The manuscript has been professionally copyedited and typeset to confirm the JBR’s formatting, but still needs proofreading by the corresponding author to ensure accuracy and correct any potential errors introduced during the editing process. It will be replaced by the online publication version.

Emerging evidence highlights the role of thyroid hormones in cancer, though findings are controversial. Research on thyroid-related traits in lung carcinogenesis is limited. Using UK Biobank data, we conducted bidirectional Mendelian randomization (MR) to assess causal links between lung cancer risk and thyroid dysfunction (hypothyroidism/hyperthyroidism) or function traits (free thyroxine [FT4], normal-range TSH). Furthermore, in the smoking-behavior stratified MR analysis, we evaluated the mediating effect of thyroid-related phenotypes on the association between smoking phenotype and lung cancer. We confirmed significant associations between lung cancer risk and hypothyroidism (hazards ratio [HR] = 1.14, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.03–1.26, P = 0.009) as well as hyperthyroidism (HR = 1.55, 95% CI = 1.29–1.87, P = 1.90×10−6) in the UKB. Moreover, the MR analysis indicated a causal effect of thyroid dysfunction on lung cancer risk (ORinverse variance weighted [IVW] = 1.09, 95% CI = 1.05–1.13, P = 3.12×10−6 for hypothyroidism; ORIVW = 1.08, 95% CI = 1.04–1.12, P = 8.14×10−5 for hyperthyroidism). We found that FT4 levels were protective against lung cancer risk (ORIVW = 0.93, 95% CI = 0.87–0.99, P = 0.030). Additionally, the stratified MR analysis demonstrated the distinct causal effect of thyroid dysfunction on lung cancer risk among smokers. Hyperthyroidism mediated the effect of smoking behavior, especially the age of smoking initiation (17.66% mediated), on lung cancer risk. Thus, thyroid dysfunction phenotypes play causal roles in lung cancer development exclusively among smokers and act as mediators in the causal pathway from smoking to lung cancer.

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer-related mortality and the second most common cancer in the United States, with approximately 238,000 new cases and 127,000 deaths in 2023[1]. The obvious clinical symptoms of lung cancer often appear in the late stage of the disease, so most patients are not diagnosed until the disease has advanced[2–3], which is accompanied by a poor prognosis and a low five-year survival rate[4]. As the burden of lung cancer increases, it is critically important to understand the in-depth pathogenesis, reveal the underlying etiology, and identify potentially modifiable risk factors to improve disease prevention.

Growing evidence has established the crucial role of thyroid hormone in regulating the physiological processes of tumor cell proliferation, differentiation, and metabolism[5–7]. Therefore, thyroid dysfunction, characterized by decreased (hypothyroidism) or increased (hyperthyroidism) secretion of thyroid hormone, may be involved in carcinogenesis[8] and is considered a potential and preventable cancer risk factor[9–10]. Previous studies investigated the association between thyroid dysfunction and cancer risk, but the findings were conflicting[11]. For example, a prospective cohort study in Western Australia found no associations between lung cancer risk and thyroid function phenotypes, including thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) and free thyroxine (FT4)[12], which contradicted the positive results from a Rotterdam study[10]. Besides, tobacco smoking is the most common established cause of lung cancer. Population-based studies have suggested that tobacco smoking is also associated with thyroid function phenotypes[13–14], with smokers exhibiting lower levels of thyroid-stimulating hormone and higher levels of thyroid hormone[15–16]. Thus, it is necessary to elaborate on whether there is a causal association between thyroid-related phenotypes (thyroid dysfunction, including hypothyroidism and hyperthyroidism, as well as thyroid function phenotypes, such as FT4 and TSH) and lung cancer risk, and to determine how thyroid-related phenotypes mediate the effect of smoking on lung cancer risk.

Despite the many advantages of observational studies, their limitations are well recognized[17], because they are vulnerable to potential confounding factors, measurement errors, and reverse causality. These issues hinder the ability to draw causal inference about the association between thyroid-related phenotypes and cancer risk. The Mendelian randomization (MR) studies, which use genetic variants as instrumental variables (IVs) to establish the causal relationships between exposure (thyroid-related phenotypes) and outcomes (lung cancer risk), are known to be less vulnerable to bias than traditional observational studies[18]. Because genetic alleles are always assigned at conception, the MR analyses are not influenced by reverse causation[19].

In the current study, we performed an observational analysis to characterize the association between thyroid dysfunction (hypothyroidism and hyperthyroidism) and lung cancer risk using the data from the UK Biobank (UKB). Furthermore, we explored the causal associations between thyroid-related phenotypes and lung cancer risk, as well as the interaction between thyroid-related phenotypes and smoking in association to lung cancer risk by a two-sample MR analysis. Besides, we aimed to determine the mediating role of thyroid-related indices in the association between smoking behavior and lung cancer risk.

UKB is a large prospective study that assessed over

We enrolled

We obtained the summary-level data of GWAS of thyroid-related phenotypes, including thyroid dysfunction for hyperthyroidism and hypothyroidism, as well as thyroid-related phenotypes for FT4 and TSH. Specific protocols of these studies contributing to the meta-analysis were described previously[21–22]. Briefly, significant SNPs associated with hypothyroidism and hyperthyroidism were extracted from

Summary-level data of GWAS of four smoking phenotypes, including smoking initiation, smoking cessation, cigarettes per day, and the initiation age of regular smoking, were obtained from a meta-analysis of 60 cohorts with up to 2.6 million individuals of the European ancestry[25]. Briefly, the meta-analysis was performed centrally using rareGWAMA and sample sizes were

Summary-level data of GWAS of lung cancer were obtained from a meta-analysis of populations in UKB, Transdisciplinary Research Into Cancer of the Lung (TRICL), and International Lung Cancer Consortium (ILCCO), including

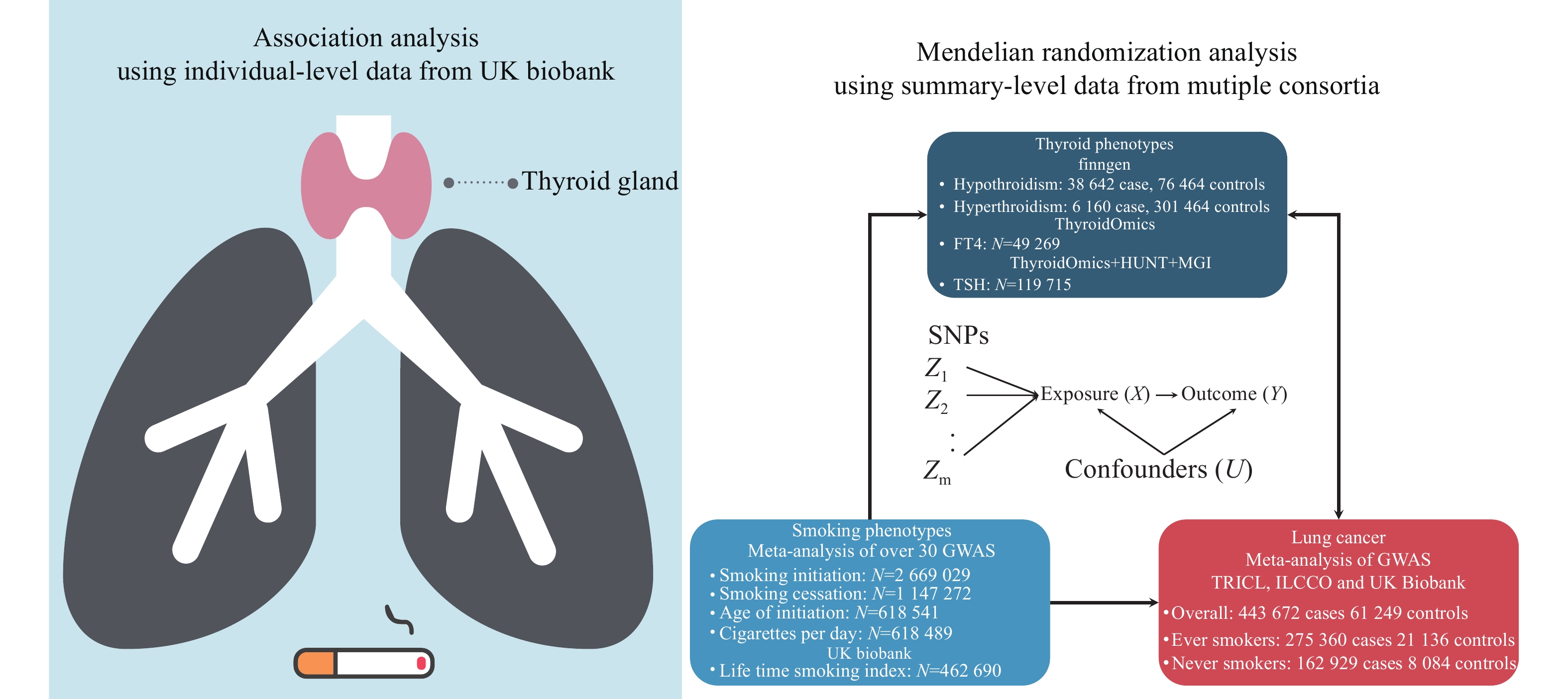

The analytic strategy consisted of two parts. First, we used individual-level data from the large perspective UKB cohort to explore the associations among smoking, thyroid dysfunction, and lung cancer risk. Second, we assessed the causal effect between thyroid-related phenotype and lung cancer risk by performing a bidirectional two-sample MR analysis. Additionally, the stratified MR analysis was performed based on smoking-behavior specific GWAS of lung cancer risk. Furthermore, we used MR-based mediation analyses to determine the mediating role of thyroid-related phenotype in the association between smoking behavior and lung cancer risk (Fig. 1).

Because FT4 and TSH were not available in UKB, the Cox proportional hazards regression models were used to assess the associations between thyroid dysfunction and lung cancer risk, adjusted for age, sex, and BMI. We also applied a multivariable logistic regression model to investigate the associations among smoking status, thyroid dysfunction, and lung cancer risk.

We used the two-sample MR analysis to assess the causal relationships between thyroid-related phenotypes (thyroid dysfunction for hyperthyroidism and hypothyroidism as well as thyroid-related phenotypes for FT4 and TSH) and lung cancer risk. SNPs associated with each exposure factor at genome-wide significance level (P < 5 × 10−8) were regarded as IVs. In addition, the approximately independent SNPs with linkage disequilibrium (LD) r2 ≤ 0.1 were filtered out by using LD clumping algorithm[28]. We harmonized all IVs for each trait to ensure that the effect allele was the same for both exposures and outcomes. Palindromic SNPs and SNPs with incompatible alleles were excluded from the current study. We also calculated the F-statistic to evaluate the strength of the Ⅳ, and SNPs with F-statistic < 10, which is considered a weak instrument effect, were deleted. Then we removed the SNPs that were significantly associated with both thyroid phenotypes and lung cancer to avoid pleiotropy.

In the primary analysis, the causal effects of thyroid-related phenotypes on lung cancer risk were estimated using the random-effects inverse-variance-weighted (MR-IVW) method[29]. In sensitivity analysis, we performed a series of different MR methods, including Egger regression (MR-Egger), maximum likelihood (MR-Maxlik)[30], robust adjusted profile score (MR-RAPS), radial (MR-Radial)[31], generalized summary-data-based MR (GSMR)[32] and MR pleiotropy residual sum and outlier (MR-PRESSO)[33], to verify the robustness of results. We also generated scatter plots of the SNP effect of each exposure factor against the effect of outcomes. Causal estimates using each instrument are displayed visually by funnel plots to assess potential asymmetries. Moreover, we carried out a leave-one-out analysis, which sequentially omitted one SNP at a time to further investigate whether the causal estimate was driven or biased by a single SNP. An additional sensitivity analysis was conducted to address overfitting bias caused by sample overlap[34]. In addition, a reverse MR analysis was used to clarify the direction of the causal relationship between thyroid-related phenotype and lung cancer risk. The stratified MR analysis was performed to explore the specific population and specific lung cancer histology.

Furthermore, the MR-based mediation analysis was performed using the product of coefficients method in a two-step MR framework, to investigate the proportion of the effect of smoking phenotypes on lung cancer risk mediated through thyroid-related phenotypes [35].

In addition, we developed a genetic risk score (GRS) by combining the effects of candidate SNPs that were associated with thyroid dysfunction from the GWAS summary-level data in the FinnGen project, and reproduced the GRS using the GWAS individual-level data in UKB[36]. We constructed a weighted GRS to integrate the genetic effects of candidate SNPs on the exposure of interest for available individual-level genotyping data. Then, we evaluated the association between GRS of thyroid dysfunction and lung cancer risk through logistic regression and the Cox proportional hazards regression model.

Normal distributed continuous variables were presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD), non-normal distributed continuous variables were described by median and interquartile range, and categorical variables were depicted as counts and percentages. The correction of type I error for multiple testing was performed by false discovery rate (FDR) method using the p.adjust package in R software. All analyses were performed using R software Version 3.6.3 (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

In the UKB cohort, hypothyroidism was significantly associated with an increased incidence of lung cancer. The Cox proportional hazards model revealed a hazards ratio (HR) of 1.18 (95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.07–1.30, P = 0.001), while logistic regression model showed an odds ratio (OR) of 1.17 (95% CI = 1.06–1.29, P = 0.002) in the overall population (Table 1). Similarly, hyperthyroidism was significantly associated with an increased incidence of lung cancer in the overall population. The Cox model yielded an HR of 1.64 (95% CI = 1.38–1.96, P = 3.96×10−8; OR = 1.64, 95% CI = 1.37–1.96, P = 7.48×10−8). For ever-smokers, the observational study showed results consistent with those in the overall population.

| Exposure | Outcome | Exposure proportion in population |

Population | Cox proportional hazards regression | Logistic regression | |||

| HR (95% CI) | P | OR (95% CI) | P | |||||

| Hypothyroidism | Lung cancer | Overallb | 1.18 (1.07, 1.30) | 0.001 | 1.17 (1.06, 1.29) | 0.002 | ||

| Ever smokersc | 1.18 (1.06, 1.31) | 0.002 | 1.17 (1.05, 1.30) | 0.004 | ||||

| Never smokersc | 1.21 (0.93, 1.57) | 0.166 | 1.20 (0.92, 1.56) | 0.181 | ||||

| Hyperthyroidism | Lung cancer | Overallb | 1.64 (1.38, 1.96) | 3.96×10−8 | 1.64 (1.37, 1.96) | 7.48×10−8 | ||

| Ever smokersc | 1.18 (1.06, 1.31) | 2.46×10−3 | 1.56 (1.28, 1.90) | 9.93×10−6 | ||||

| Never smokersc | 2.22 (1.44, 3.44) | 3.38×10−4 | 2.23 (1.44, 3.47) | 3.32×10−4 | ||||

| Smoke | Hypothyroidism | Overallc | – | – | 1.07 (1.04, 1.09) | 5.92×10−9 | ||

| Smoke | Hyperthyroidism | Overallc | – | – | 1.16 (1.11, 1.22) | 1.32×10−9 | ||

| aThe data of FT4 and TSH were not available in the UK biobank.bModel adjusted for smoke status, age, sex, and BMI.cModel adjusted for age, sex, and BMI.Abbreviations: HR, hazards ratio; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval. | ||||||||

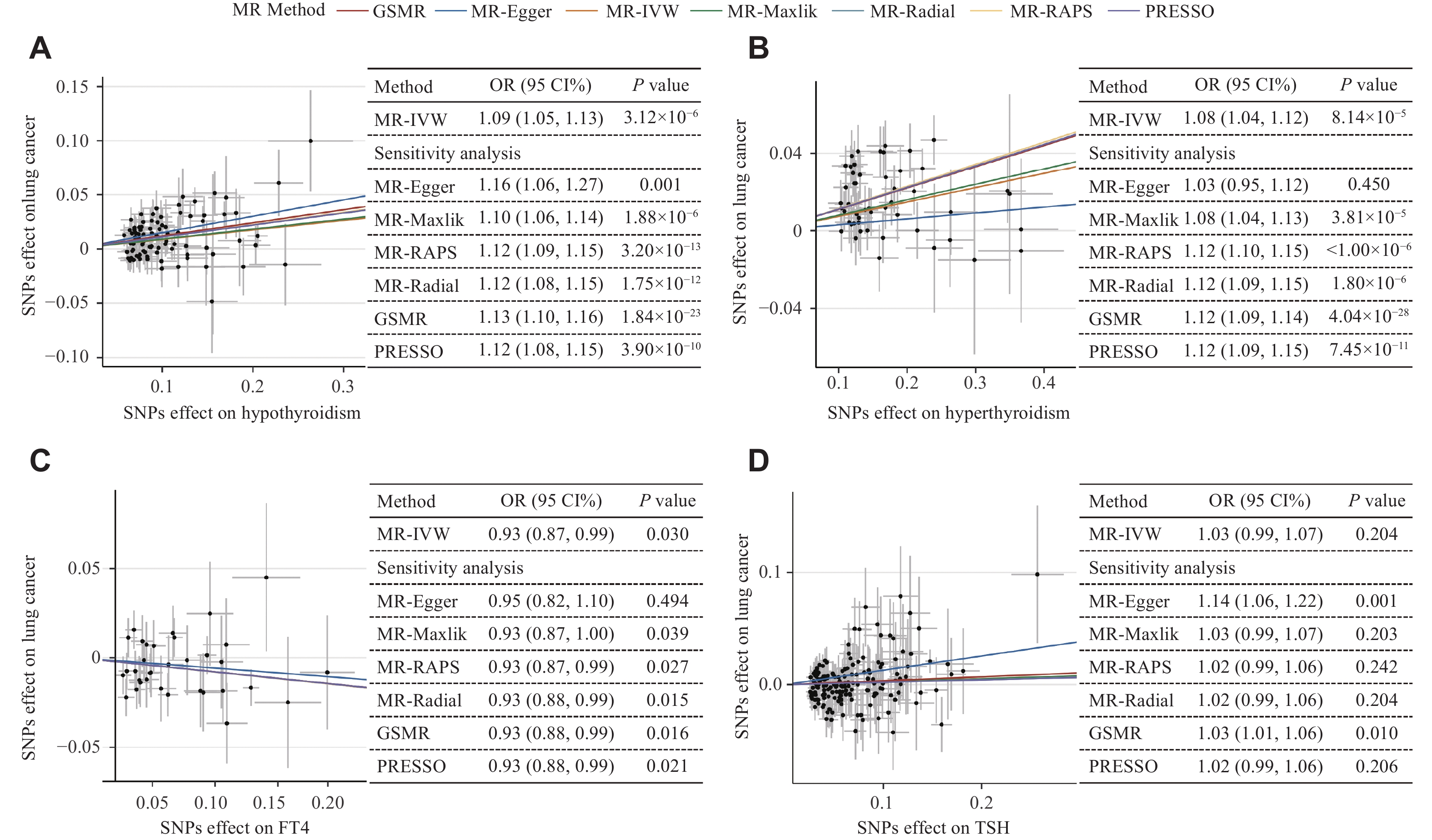

To explore the causal associations between thyroid-related phenotypes and lung cancer risk, we performed two-sample MR analysis. After excluding SNPs according to the criteria of IVs, we obtained a final set of 89 SNPs for hypothyroidism, 51 SNPs for hyperthyroidism, 34 SNPs for FT4 and 173 SNP for TSH. The instrumental strengths (F statistics) for all included SNPs were larger than 10, indicating little weak instrumental bias (Supplementary Tables 4–7, available online). As shown in Fig. 2, there was some strong evidence that both hypothyroidism and hyperthyroidism were the causal risk factors for lung cancer. In the primary analysis, we applied IVW and obtained OR inverse variance weighted [IVW] of 1.09 (95% CI = 1.05–1.13, P = 3.12×10−6) and 1.08 (95% CI = 1.04–1.12, P = 8.14×10−5) for hypothyroidism and hyperthyroidism, respectively. Additionally, we found that a per SD-increase in FT4 concentration was negatively associated with lung cancer risk (ORIVW = 0.93, 95% CI = 0.87–0.99, P = 0.030). Meanwhile, there was no evidence supporting the causal effect of TSH on lung cancer risk. Furthermore, a series of other MR methods yielded consistent results, confirming the robustness of the causal effects between the three thyroid-related phenotypes and lung cancer risk (Fig. 2).

In the sensitivity analysis, the estimated causal effects of each hypothyroidism- and hyperthyroidism-associated SNP were symmetrically distributed in the funnel plot (Supplementary Fig. 1–2, available online). The leave-one-out analysis did not identify any variants with an inflationary impact on the causal effect estimation (Supplementary Fig. 3–6, available online). The findings from the MRlap analysis consistently supported causal associations between thyroid-related phenotypes and the risk of lung cancer, and there was no evidence of directional pleiotropy based on the MR-Egger intercept value. Additionally, positive effects were observed for hypothyroidism and the risk of squamous cell carcinoma (ORIVW = 1.23, 95% CI = 1.15–1.31, P = 6.84×10−10) and small cell carcinoma (ORIVW = 1.12, 95% CI = 1.03–1.20, P = 4.70×10−3). Consistent with the overall lung cancer results, we also observed the effect of hyperthyroidism on squamous cell carcinoma (ORIVW = 1.16, 95% CI = 1.10–1.23, P = 6.08×10−18) and the effect of FT4 on small cell carcinoma (ORIVW = 0.81, 95% CI = 0.66–0.99, P = 0.004). The MR analysis showed that TSH had an effect estimate consistent with the decreased risk of adenocarcinoma (ORIVW = 1.12, 95% CI = 1.06–1.20, P = 2.26×10−4) (Supplementary Fig. 7, available online]).

Moreover, reverse MR analysis showed some evidence that the increased risk of lung cancer was also causally associated with higher risk of hyperthyroidism (ORIVW = 1.11, 95% CI = 1.00–1.22, P = 0.040), higher level of FT4 (βIVW = 0.04, 95%CI = 0.01–0.08, P = 0.025), lower level of TSH (βIVW = −0.04, 95%CI = −0.06–−0.01, P = 0.003) (Supplementary Fig. 8A–8C, available online). There was no clear evidence of the causal association between lung cancer risk and hypothyroidism (Supplementary Fig. 8D, available online).

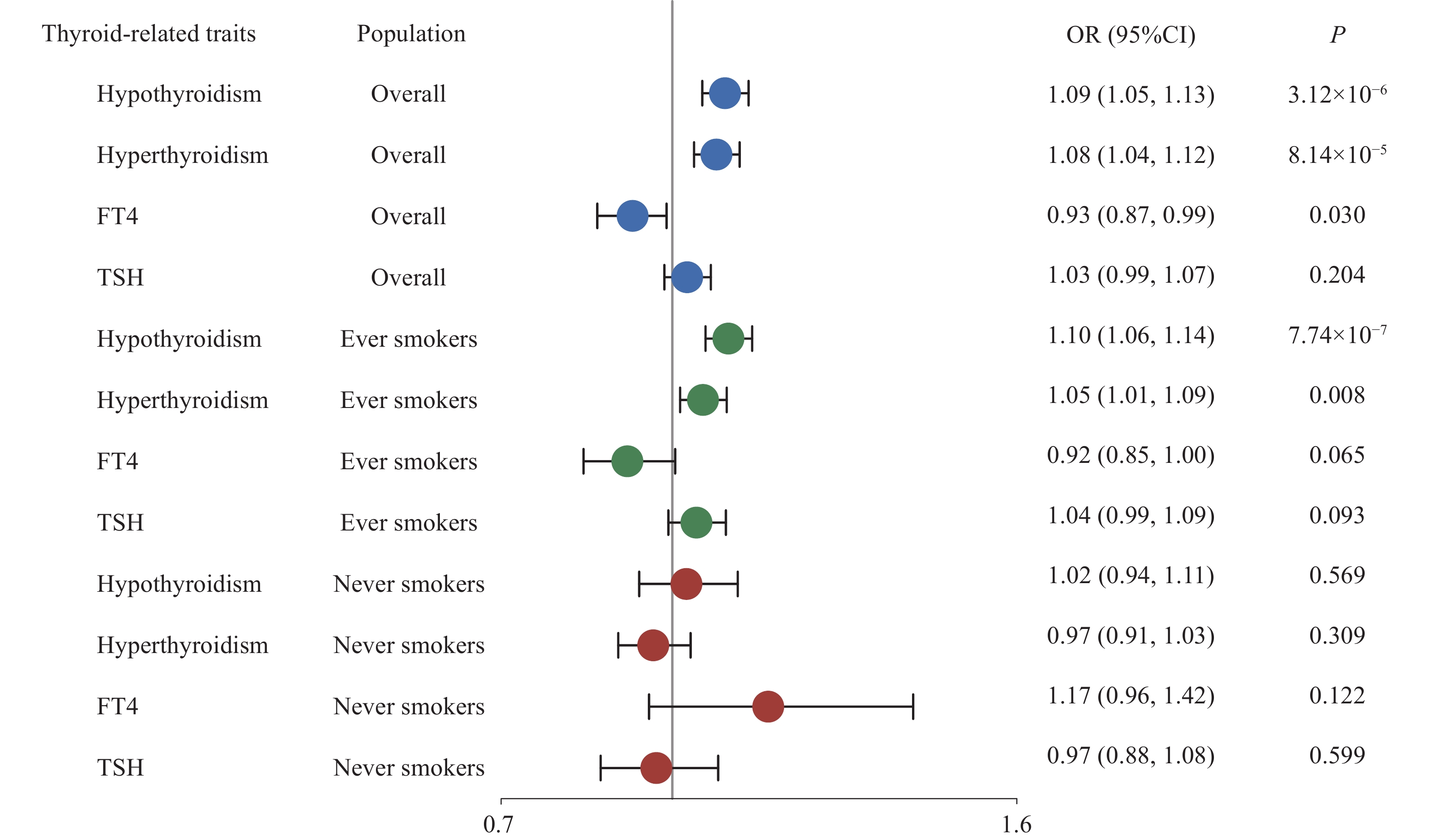

After applying an FDR correction for multiple comparisons, the MR analysis indicated potential causal effects of smoking phenotypes on thyroid dysfunction. Smoking initiation was associated with a higher risk of both hypothyroidism (ORIVW = 1.19, 95% CI = 1.07–1.33, q-FDR = 0.004) and hyperthyroidism (ORIVW = 1.56, 95% CI = 1.30–1.88, q-FDR = 3.62×10−5), but lower levels of TSH (βIVW = −0.10, 95% CI = −0.15–−0.05, q-FDR = 4.21×10−4). As for the cigarette per day, the effects were reversed for FT4 (βIVW = 0.13, 95% CI = 0.04–0.21, q-FDR = 0.016) and TSH (βIVW = −0.12, 95% CI = −0.19–−0.06, q-FDR = 0.001). An increase in the age of initiation was causally associated with a lower risk of hypothyroidism (ORIVW = 0.31, 95% CI = 0.15 to 0.63, q-FDR = 0.004). Additionally, a one-SD increase in lifetime smoking index was causally associated with an increased risk of hypothyroidism (ORIVW = 1.73, 95% CI = 1.29–2.34, q-FDR = 0.001) but a decreased level of TSH (βIVW = −0.11, 95% CI = −0.18–−0.03, q-FDR = 0.022), respectively (Supplementary Fig. 9 [available online]) and Fig. 3).

Further, stratified MR analysis was used to explore the independent causal effect of thyroid-related phenotypes. Both hypothyroidism and hyperthyroidism were causally associated with lung cancer only among ever-smokers, while no evidence was found in non-smokers (Fig. 4). Moreover, the direction of the causal effect of each phenotype remained consistent with that in the overall population (ORIVW = 1.10, 95% CI = 1.06–1.14, P = 7.74×10−7 for hypothyroidism; ORIVW = 1.05, 95% CI = 1.01 –1.09, P = 0.008 for hyperthyroidism). A series of sensitivity analyses showed a robust causal association between thyroid dysfunction and lung cancer risk among the ever-smoke population (Supplementary Fig. 10–16, available online).

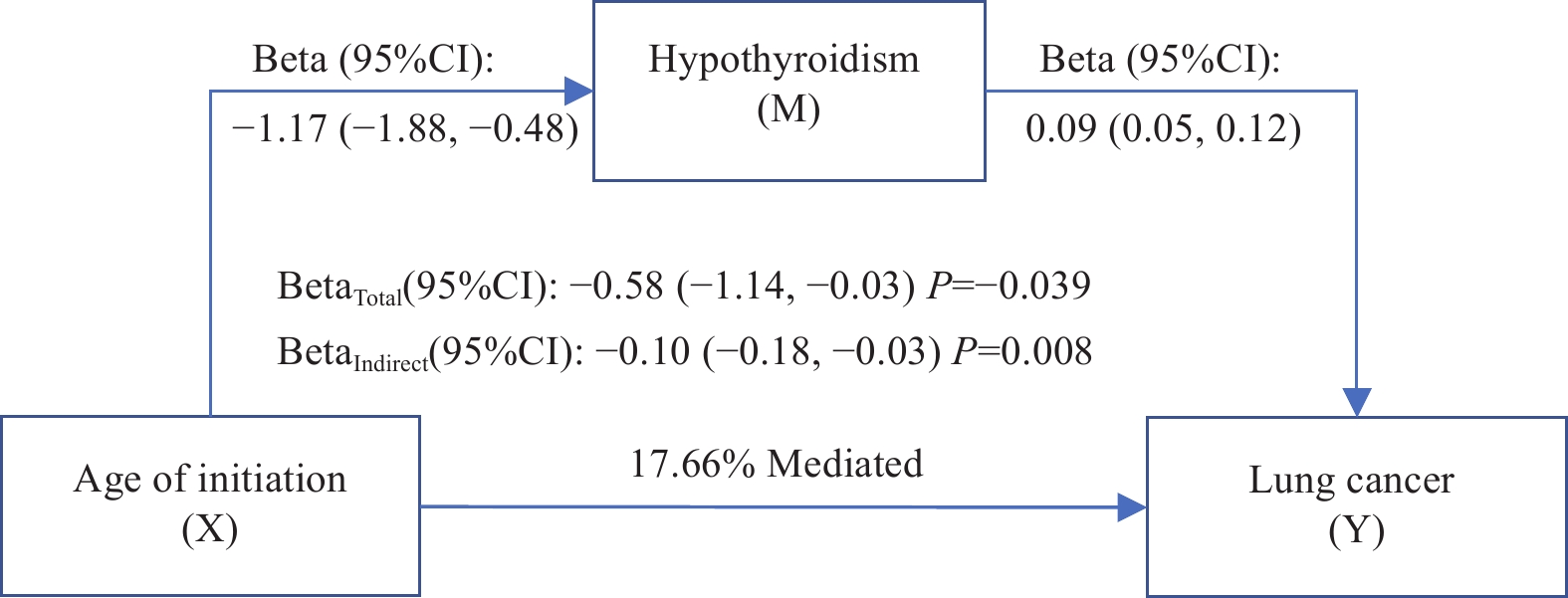

The mediating effects of thyroid-related phenotypes on the association between smoking phenotypes and lung cancer were estimated by a two-step MR analysis. The causal association of smoking phenotypes and lung cancer with thyroid-related phenotypes was examined by using the two-sample MR analysis (Fig. 3). The proportion of hypothyroidism mediated the total effect of the age of smoking initiation on lung cancer risk was 17.66% (Fig. 5). Additionally, the proportion of the total effect of smoking initiation on lung cancer risk mediated by hypothyroidism and hyperthyroidism was estimated to be 2.02% (Supplementary Fig. 17A, available online) and 4.31% (Supplementary Fig. 17B, available online), respectively. Hypothyroidism mediated 2.49% of the total effect of lifetime smoking index on lung cancer risk (Supplementary Fig. 17C, available online).

Subsequently, similar evidence was found to support the associations between genetically predicted hypothyroidism and hyperthyroidism with the risk of lung cancer in the overall population of the UKB cohort study. (Supplementary Table 8, available online).

To the best of our knowledge, the current study is the first attempt to explore the causal relationship among smoking, thyroid-related phenotypes, and lung cancer using both observational and genetic evidence. Our findings suggested a robust causal association between thyroid-related phenotypes (hypothyroidism, hyperthyroidism, TSH) and lung cancer. Through stratified analysis by smoking status, we observed that these causal associations between thyroid dysfunction and lung cancer presented exclusively in smokers. Additionally, there was sufficient evidence for reverse causal associations between thyroid-related phenotypes and lung cancer, except in the case of hypothyroidism.

Observational studies have indicated that both thyroid hormone levels and thyroid disorder were closely associated with overall cancer risk, including breast cancer, prostate and colorectal cancers[37-40]. While few previous studies have addressed the association between thyroid-related phenotypes and lung cancer risk, our investigation contributes to the literature by providing interesting and promising results. Notably, our study highlights the causal role of thyroid dysfunction in lung cancer, especially among smokers, which is consistent with previous epidemiological findings[10,38]. The underlying mechanism may involve the effect of tobacco smoking on thyroid gland function[41]. Tobacco contains cyanide, which is converted to chemical thiocyanate when smoked. Thiocyanate is known to interfere with thyroid-related phenotypes through inhibiting iodine uptake into the thyroid gland and reducing thyroid hormone production[42-44]. This suggests that smoking may lead to disruptions of thyroid hormone production, resulting in thyroid dysfunction and an increased risk of lung cancer.

As for the association between thyroid hormone and lung cancer, the current results are inconsistent with those of previous studies. In the Rotterdam study[10], higher FT4 levels were associated with an increased risk of lung cancer, while no significant association was found between TSH levels and lung cancer risk. In contrast, Chen et al[12] found that lower TSH and higher FT4 levels predicted the incidence of prostate cancer but not lung cancer in Western Australia. Unsurprisingly, the findings of these prospective cohort studies are also conflicting. Possible explanations behind these discrepancies include unmeasured confounding factors or reverse causality. Although efforts have been made to adjust for obvious confounders, traditional statistical methods struggle to fully account for these factors in observational studies. Another plausible reason could be insufficient power because of the small sample size of lung cancer in each study (ranged from 41 to 201).

Inconsistencies also exit between the current study and previous MR results[45], which may be attributed to several factors, including differences in phenotype definitions, GWAS sample size, and the selection of instrumental variables. First, the phenotypes used in Wang's study were "hypothyroidism, strict autoimmune" and "autoimmune hyperthyroidism", whereas the current study included "hypothyroidism (congenital or acquired)", "autoimmune hyperthyroidism", and "thyrotoxicosis". Second, the summary-level data of lung cancer in the current study were obtained from a meta-analysis of populations in the UKB, TRICL and ILLCO, including

In general, we can confirm that abnormal thyroid hormone levels are associated with the development of lung cancer, which aligns with the role of thyroid hormone in cancer pathogenesis. Serval studies have reported that immune-related thyroid dysfunction is associated with the response to anti-PD-1 therapy among patients with NSCLC[46], in which Luo[46] has identified that genetic differences in immunity may contribute to toxicity and outcomes in immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy. Our bidirectional MR results between thyroid dysfunction and lung cancer provided insights into the associations among underlying autoimmunity, immune-related thyroid dysfunction, and immunotherapy outcomes.

It is worth noting that our results indicate that hereditary hypothyroidism increases the risk of lung cancer, especially among smokers. Some studies have elucidated the underlying mechanisms by which hypothyroidism contributes to the development of lung cancer. Evidence from experimental animals[47] and clinical studies[46] suggests that hypothyroidism affects the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis and is associated with mitochondrial dysfunction, leading to an increased production of reactive oxygen species (ROS)[49]. The tumor-promoting effect of ROS in lung cancer has been well demonstrated. Accumulating evidence[50-52] has also suggested that ROS plays a major role in the initiation, promotion and progression of cancer by regulating signal molecules involved in cell proliferation, angiogenesis, and alteration of the migration and invasion program[52-53]. Another potential mechanism may involve the derivative of L-thyroxine tetrac[54]. Tetrac is a minor product in normal thyroid physiology, which inhibits tumor growth by blocking the binding of thyroid hormones to the plasma membrane receptor integrin αvβ3[55–57]. Increasing evidence suggests that tetrac is involved in anti-angiogenic and anti-tumor activities, including the inhibition of cancer cell proliferation[58–59], the enhancement of cancer cell apoptosis, and the disruption of multiple angiogenic pathways. Furthermore, tetrac has been shown to effectively inhibit the growth of non-small cell lung cancer in vitro as well as in chick chorioallantoic membrane assay and murine xenograft models[60].

The current study has several strengths. First, the MR analysis was used to identify the association between thyroid dysfunction and lung cancer risk to avoid potential false associations and reverse causality, which are common in observation studies. Second, we applied a series of MR methods and sensitivity analyses to verify the robust causal effect of thyroid dysfunction on lung cancer and conducted an independent validation using individual-level data from a large prospective cohort. Third, this study included the largest sample of lung cancer cases and thyroid function-related phenotypes to date, ensuring a sufficient power to infer causality. Fourth, we also performed a bidirectional MR analysis to clarify the direction of the association between thyroid dysfunction and lung cancer. Finally, we found that the effect of smoking on lung cancer risk might be mediated through thyroid-related phenotypes.

However, we acknowledge that the current study has some limitations. First, our study is limited to the European ancestry, thus, the findings should be extrapolated to the other populations with caution. Second, because of lacking thyroid hormone level data in the UKB, we were unable to explore the dose-response relationship between TSH and FT4 levels and lung cancer risk. Third, further biological experiments are warranted to explore the causal mechanism underlying the association between thyroid-related phenotypes and lung carcinogenesis.

In conclusion, both observational and causal evidence support the effect of thyroid dysfunction on lung cancer, especially in smokers. Specifically, both hypothyroidism and hyperthyroidism were associated with an increased risk of lung cancer. The findings of the current study may draw attention to the role of thyroid dysfunction in lung carcinogenesis and provide some insights into the biological mechanisms underlying lung cancer prevention and clinical practice. Whether the effects of thyroid dysfunction and hormones are meaningful as potential intervention targets requires further investigation to unravel the molecular pathways involved.

The study was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 82220108002 to F.C., 82273737 to R.Z., and 82473728 to Y.W.), US National Institutes of Health (Grant Nos. CA209414, HL060710, and ES000002 to D.C.C.; CA209414 and CA249096 to Y.L.), and Priority Academic Program Development of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions (PAPD). R.Z. was partially supported by the Qing Lan Project of the Higher Education Institutions of Jiangsu Province and the Outstanding Young Level Academic Leadership Training Program of Nanjing Medical University.

We thank all the GWAS consortia involved in this work for making the summary statistics publicly available. We are grateful to all the investigators and participants who contributed to these studies.

CLC number: R734.2, Document code: A

The authors reported no conflict of interests.

| [1] |

Siegel RL, Miller KD, Wagle NS, et al. Cancer statistics, 2023[J]. CA Cancer J Clin, 2023, 73(1): 17–48. doi: 10.3322/caac.21763

|

| [2] |

Postmus PE, Kerr KM, Oudkerk M, et al. Early and locally advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC): ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up[J]. Ann Oncol, 2017, 28(S4): iv1–iv21. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28881918/

|

| [3] |

Hirsch FR, Scagliotti GV, Mulshine JL, et al. Lung cancer: current therapies and new targeted treatments[J]. Lancet, 2017, 389(10066): 299–311. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30958-8

|

| [4] |

Garon EB, Hellmann MD, Rizvi NA, et al. Five-year overall survival for patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer treated with pembrolizumab: results from the phase I KEYNOTE-001 study[J]. J Clin Oncol, 2019, 37(28): 2518–2527. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.00934

|

| [5] |

Krashin E, Piekiełko-Witkowska A, Ellis M, et al. Thyroid hormones and cancer: a comprehensive review of preclinical and clinical studies[J]. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne), 2019, 10: 59. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2019.00059

|

| [6] |

Chi HC, Chen C, Tsai MM, et al. Molecular functions of thyroid hormones and their clinical significance in liver-related diseases[J]. Biomed Res Int, 2013, 2013: 601361. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23878812/

|

| [7] |

Liu YC, Yeh CT, Lin KH. Molecular functions of thyroid hormone signaling in regulation of cancer progression and anti-apoptosis[J]. Int J Mol Sci, 2019, 20(20): 4986. doi: 10.3390/ijms20204986

|

| [8] |

Journy NMY, Bernier MO, Doody MM, et al. Hyperthyroidism, hypothyroidism, and cause-specific mortality in a large cohort of women[J]. Thyroid, 2017, 27(8): 1001–1010. doi: 10.1089/thy.2017.0063

|

| [9] |

Rinaldi S, Plummer M, Biessy C, et al. Thyroid-stimulating hormone, thyroglobulin, and thyroid hormones and risk of differentiated thyroid carcinoma: the EPIC study[J]. J Natl Cancer Inst, 2014, 106(6): dju097. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dju097

|

| [10] |

Khan SR, Chaker L, Ruiter R, et al. Thyroid function and cancer risk: the rotterdam study[J]. J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 2016, 101(12): 5030–5036. doi: 10.1210/jc.2016-2104

|

| [11] |

Tran TVT, Kitahara CM, de Vathaire F, et al. Thyroid dysfunction and cancer incidence: a systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. Endocr Relat Cancer, 2020, 27(4): 245–259. doi: 10.1530/ERC-19-0417

|

| [12] |

Chan YX, Knuiman MW, Divitini ML, et al. Lower TSH and higher free thyroxine predict incidence of prostate but not breast, colorectal or lung cancer[J]. Eur J Endocrinol, 2017, 177(4): 297–308. doi: 10.1530/EJE-17-0197

|

| [13] |

Jorde R, Sundsfjord J. Serum TSH levels in smokers and non-smokers. The 5th Tromsø study[J]. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes, 2006, 114(7): 343–347. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-924264

|

| [14] |

Fisher CL, Mannino DM, Herman WH, et al. Cigarette smoking and thyroid hormone levels in males[J]. Int J Epidemiol, 1997, 26(5): 972–977. doi: 10.1093/ije/26.5.972

|

| [15] |

Prummel MF, Wiersinga WM. Smoking and risk of Graves' disease[J]. JAMA, 1993, 269(4): 479–482. doi: 10.1001/jama.1993.03500040045034

|

| [16] |

Gruppen EG, Kootstra-Ros J, Kobold AM, et al. Cigarette smoking is associated with higher thyroid hormone and lower TSH levels: the PREVEND study[J]. Endocrine, 2020, 67(3): 613–622. doi: 10.1007/s12020-019-02125-2

|

| [17] |

Sekula P, Del Greco MF, Pattaro C, et al. Mendelian randomization as an approach to assess causality using observational data[J]. J Am Soc Nephrol, 2016, 27(11): 3253–3265. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2016010098

|

| [18] |

Davies NM, Holmes MV, Davey Smith G. Reading Mendelian randomisation studies: a guide, glossary, and checklist for clinicians[J]. BMJ, 2018, 362: k601. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30002074/

|

| [19] |

Swanson SA, Tiemeier H, Ikram MA, et al. Nature as a trialist?: deconstructing the analogy between Mendelian randomization and randomized trials[J]. Epidemiology, 2017, 28(5): 653–659. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0000000000000699

|

| [20] |

Sudlow C, Gallacher J, Allen N, et al. UK biobank: an open access resource for identifying the causes of a wide range of complex diseases of middle and old age[J]. PLoS Med, 2015, 12(3): e1001779. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001779

|

| [21] |

Psaty BM, O'donnell CJ, Gudnason V, et al. Cohorts for heart and aging research in genomic epidemiology (CHARGE) consortium: design of prospective meta-analyses of genome-wide association studies from 5 cohorts[J]. Circ: Cardiovasc Genet, 2009, 2(1): 73–80. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.108.829747

|

| [22] |

Kurki MI, Karjalainen J, Palta P, et al. FinnGen provides genetic insights from a well-phenotyped isolated population[J]. Nature, 2023, 613(7944): 508–518. doi: 10.1038/s41586-022-05473-8

|

| [23] |

Teumer A, Chaker L, Groeneweg S, et al. Genome-wide analyses identify a role for SLC17A4 and AADAT in thyroid hormone regulation[J]. Nat Commun, 2018, 9(1): 4455. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-06356-1

|

| [24] |

Zhou W, Brumpton B, Kabil O, et al. GWAS of thyroid stimulating hormone highlights pleiotropic effects and inverse association with thyroid cancer[J]. Nat Commun, 2020, 11(1): 3981. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-17718-z

|

| [25] |

Saunders GRB, Wang X, Chen F, et al. Genetic diversity fuels gene discovery for tobacco and alcohol use[J]. Nature, 2022, 612(7941): 720–724. doi: 10.1038/s41586-022-05477-4

|

| [26] |

Wootton RE, Richmond RC, Stuijfzand BG, et al. Evidence for causal effects of lifetime smoking on risk for depression and schizophrenia: a Mendelian randomisation study[J]. Psychol Med, 2020, 50(14): 2435–2443. doi: 10.1017/S0033291719002678

|

| [27] |

McKay JD, Hung RJ, Han Y, et al. Large-scale association analysis identifies new lung cancer susceptibility loci and heterogeneity in genetic susceptibility across histological subtypes[J]. Nat Genet, 2017, 49(7): 1126–1132. doi: 10.1038/ng.3892

|

| [28] |

Chang CC, Chow CC, Tellier LC, et al. Second-generation PLINK: rising to the challenge of larger and richer datasets[J]. GigaScience, 2015, 4: 7. doi: 10.1186/s13742-015-0047-8

|

| [29] |

Burgess S, Butterworth A, Thompson SG. Mendelian randomization analysis with multiple genetic variants using summarized data[J]. Genet Epidemiol, 2013, 37(7): 658–665. doi: 10.1002/gepi.21758

|

| [30] |

Waterworth DM, Ricketts SL, Song K, et al. Genetic variants influencing circulating lipid levels and risk of coronary artery disease[J]. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol, 2010, 30(11): 2264–2276. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.109.201020

|

| [31] |

Bowden J, Spiller W, Del Greco MF, et al. Improving the visualization, interpretation and analysis of two-sample summary data Mendelian randomization via the Radial plot and Radial regression[J]. Int J Epidemiol, 2018, 47(6): 2100. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyy265

|

| [32] |

Zhu Z, Zheng Z, Zhang F, et al. Causal associations between risk factors and common diseases inferred from GWAS summary data[J]. Nat Commun, 2018, 9(1): 224. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-02317-2

|

| [33] |

Verbanck M, Chen CY, Neale B, et al. Detection of widespread horizontal pleiotropy in causal relationships inferred from Mendelian randomization between complex traits and diseases[J]. Nat Genet, 2018, 50(5): 693–698. doi: 10.1038/s41588-018-0099-7

|

| [34] |

Mounier N, Kutalik Z. Bias correction for inverse variance weighting Mendelian randomization[J]. Genet Epidemiol, 2023, 47(4): 314–331. doi: 10.1002/gepi.22522

|

| [35] |

Carter AR, Sanderson E, Hammerton G, et al. Mendelian randomisation for mediation analysis: current methods and challenges for implementation[J]. Eur J Epidemiol, 2021, 36(5): 465–478. doi: 10.1007/s10654-021-00757-1

|

| [36] |

Xin J, Jiang X, Ben S, et al. Association between circulating vitamin E and ten common cancers: evidence from large-scale Mendelian randomization analysis and a longitudinal cohort study[J]. BMC Med, 2022, 20(1): 168. doi: 10.1186/s12916-022-02366-5

|

| [37] |

Gómez-Izquierdo J, Filion KB, Boivin JF, et al. Subclinical hypothyroidism and the risk of cancer incidence and cancer mortality: a systematic review[J]. BMC Endocr Disord, 2020, 20(1): 83. doi: 10.1186/s12902-020-00566-9

|

| [38] |

Hellevik AI, Asvold BO, Bjøro T, et al. Thyroid function and cancer risk: a prospective population study[J]. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev, 2009, 18(2): 570–574. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0911

|

| [39] |

Angelousi AG, Anagnostou VK, Stamatakos MK, et al. Mechanisms in endocrinology: primary HT and risk for breast cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. Eur J Endocrinol, 2012, 166(3): 373–381. doi: 10.1530/EJE-11-0838

|

| [40] |

L'Heureux A, Wieland DR, Weng CH, et al. Association between thyroid disorders and colorectal cancer risk in adult patients in Taiwan[J]. JAMA Netw Open, 2019, 2(5): e193755. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.3755

|

| [41] |

Wiersinga WM. Smoking and thyroid[J]. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf), 2013, 79(2): 145–151. doi: 10.1111/cen.12222

|

| [42] |

Knight BA, Shields BM, He X, et al. Effect of perchlorate and thiocyanate exposure on thyroid function of pregnant women from South-West England: a cohort study[J]. Thyroid Res, 2018, 11: 9. doi: 10.1186/s13044-018-0053-x

|

| [43] |

Erdoǧan MF. Thiocyanate overload and thyroid disease[J]. Biofactors, 2003, 19(3-4): 107–111. doi: 10.1002/biof.5520190302

|

| [44] |

Sawicka-Gutaj N, Gutaj P, Sowinski J, et al. Influence of cigarette smoking on thyroid gland-an update[J]. Endokrynol Pol, 2014, 65(1): 54–62. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24549603/

|

| [45] |

Wang X, Liu X, Li Y, et al. The causal relationship between thyroid function, autoimune thyroid dysfunction and lung cancer: a mendelian randomization study[J]. BMC Pulm Med, 2023, 23(1): 338. doi: 10.1186/s12890-023-02588-0

|

| [46] |

Luo J, Martucci VL, Quandt Z, et al. Immunotherapy-mediated thyroid dysfunction: genetic risk and impact on outcomes with PD-1 blockade in non-small cell lung cancer[J]. Clin Cancer Res, 2021, 27(18): 5131–5140. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-21-0921

|

| [47] |

Wang L, He W, Xu X, et al. Pathological changes and oxidative stress of the HPG axis in hypothyroid rat[J]. J Mol Endocrinol, 2021, 67(3): 107–119. doi: 10.1530/JME-21-0095

|

| [48] |

Nanda N, Bobby Z, Hamide A. Oxidative stress and protein glycation in primary hypothyroidism. Male/female difference[J]. Clin Exp Med, 2008, 8(2): 101–108. doi: 10.1007/s10238-008-0164-0

|

| [49] |

Peixoto MS, de Vasconcelos ESA, Andrade IS, et al. Hypothyroidism induces oxidative stress and DNA damage in breast[J]. Endocr Relat Cancer, 2021, 28(7): 505–519. doi: 10.1530/ERC-21-0010

|

| [50] |

Azad N, Rojanasakul Y, Vallyathan V. Inflammation and lung cancer: roles of reactive oxygen/nitrogen species[J]. J Toxicol Environ Health B Crit Rev, 2008, 11(1): 1–15. doi: 10.1080/10937400701436460

|

| [51] |

Reczek CR, Chandel NS. The two faces of reactive oxygen species in cancer[J]. Annu Rev Cancer Biol, 2017, 1: 79–98. doi: 10.1146/annurev-cancerbio-041916-065808

|

| [52] |

Kometani T, Yoshino I, Miura N, et al. Benzo[a]pyrene promotes proliferation of human lung cancer cells by accelerating the epidermal growth factor receptor signaling pathway[J]. Cancer Lett, 2009, 278(1): 27–33. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2008.12.017

|

| [53] |

Weinberg F, Hamanaka R, Wheaton WW, et al. Mitochondrial metabolism and ROS generation are essential for Kras-mediated tumorigenicity[J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2010, 107(19): 8788–8793. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1003428107

|

| [54] |

Wu SY, Green WL, Huang W, et al. Alternate pathways of thyroid hormone metabolism[J]. Thyroid, 2005, 15(8): 943–958. doi: 10.1089/thy.2005.15.943

|

| [55] |

Cheng SY, Leonard JL, Davis PJ. Molecular aspects of thyroid hormone actions[J]. Endocr Rev, 2010, 31(2): 139–170. doi: 10.1210/er.2009-0007

|

| [56] |

Davis PJ, Leonard JL, Davis FB. Mechanisms of nongenomic actions of thyroid hormone[J]. Front Neuroendocrinol, 2008, 29(2): 211–218. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2007.09.003

|

| [57] |

Schmohl KA, Müller AM, Wechselberger A, et al. Thyroid hormones and tetrac: new regulators of tumour stroma formation via integrin αvβ3[J]. Endocr Relat Cancer, 2015, 22(6): 941–952. doi: 10.1530/ERC-15-0245

|

| [58] |

Schmohl KA, Nelson PJ, Spitzweg C. Tetrac as an anti-angiogenic agent in cancer[J]. Endocr Relat Cancer, 2019, 26(6): R287–R304. doi: 10.1530/ERC-19-0058

|

| [59] |

Davis PJ, Mousa SA, Lin HY. Nongenomic actions of thyroid hormone: the integrin component[J]. Physiol Rev, 2021, 101(1): 319–352. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00038.2019

|

| [60] |

Mousa SA, Yalcin M, Bharali DJ, et al. Tetraiodothyroacetic acid and its nanoformulation inhibit thyroid hormone stimulation of non-small cell lung cancer cells in vitro and its growth in xenografts[J]. Lung Cancer, 2012, 76(1): 39–45. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2011.10.003

|

| Exposure | Outcome | Exposure proportion in population |

Population | Cox proportional hazards regression | Logistic regression | |||

| HR (95% CI) | P | OR (95% CI) | P | |||||

| Hypothyroidism | Lung cancer | Overallb | 1.18 (1.07, 1.30) | 0.001 | 1.17 (1.06, 1.29) | 0.002 | ||

| Ever smokersc | 1.18 (1.06, 1.31) | 0.002 | 1.17 (1.05, 1.30) | 0.004 | ||||

| Never smokersc | 1.21 (0.93, 1.57) | 0.166 | 1.20 (0.92, 1.56) | 0.181 | ||||

| Hyperthyroidism | Lung cancer | Overallb | 1.64 (1.38, 1.96) | 3.96×10−8 | 1.64 (1.37, 1.96) | 7.48×10−8 | ||

| Ever smokersc | 1.18 (1.06, 1.31) | 2.46×10−3 | 1.56 (1.28, 1.90) | 9.93×10−6 | ||||

| Never smokersc | 2.22 (1.44, 3.44) | 3.38×10−4 | 2.23 (1.44, 3.47) | 3.32×10−4 | ||||

| Smoke | Hypothyroidism | Overallc | – | – | 1.07 (1.04, 1.09) | 5.92×10−9 | ||

| Smoke | Hyperthyroidism | Overallc | – | – | 1.16 (1.11, 1.22) | 1.32×10−9 | ||

| aThe data of FT4 and TSH were not available in the UK biobank.bModel adjusted for smoke status, age, sex, and BMI.cModel adjusted for age, sex, and BMI.Abbreviations: HR, hazards ratio; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval. | ||||||||