| Citation: | Renqi Li, Qiuting Zeng, Muhuo Ji, Yue Zhang, Mingjie Mao, Shanwu Feng, Manlin Duan, Zhiqiang Zhou. Oxytocin ameliorates cognitive impairments by attenuating excitation/inhibition imbalance of neurotransmitters acting on parvalbumin interneurons in a mouse model of sepsis-associated encephalopathy[J]. The Journal of Biomedical Research, 2025, 39(2): 132-145. DOI: 10.7555/JBR.37.20230318 |

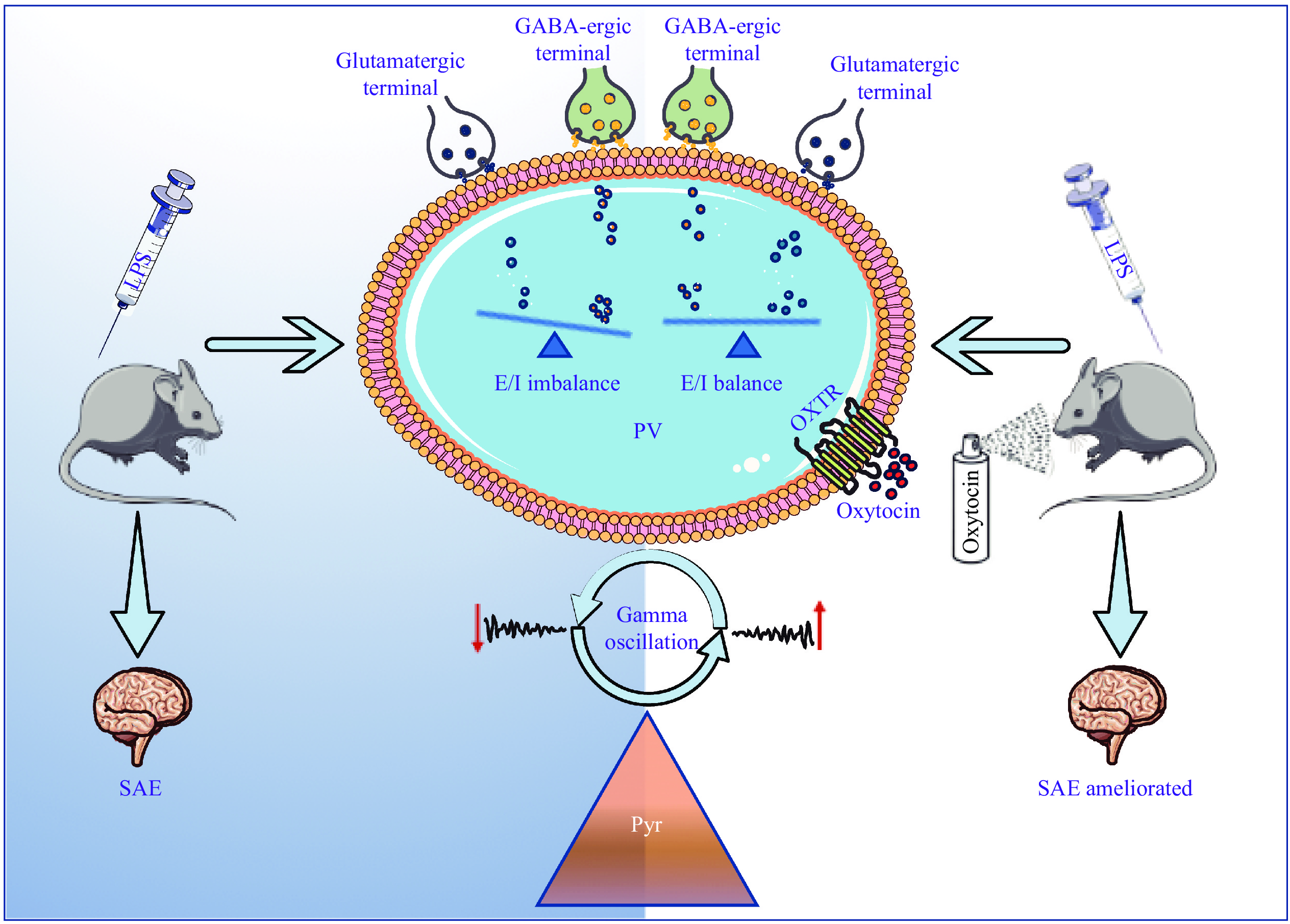

Inflammation plays a crucial role in the initiation and progression of sepsis and induces alterations in brain neurotransmission, thereby contributing to the development of sepsis-associated encephalopathy (SAE). Parvalbumin (PV) interneurons are pivotal contributors to cognitive processes and have been implicated in various central nervous system dysfunctions, including SAE. Oxytocin, known for its ability to augment the firing rate of gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA)-ergic interneurons and directly stimulate inhibitory interneurons to enhance the tonic inhibition of pyramidal neurons, has prompted an investigation into its potential therapeutic effects on cognitive dysfunction in SAE. In the current study, we administered intranasal oxytocin to SAE mice induced by lipopolysaccharide. Behavioral assessments, including open field, Y-maze, and fear conditioning, were used to evaluate cognitive performance. Golgi staining revealed hippocampal synaptic deterioration, local field potential recordings showed weakened gamma oscillations, and immunofluorescence (IF) staining demonstrated decreased PV expression in the cornu ammonis 1 (CA1) region of the hippocampus following lipopolysaccharide treatment, all of which were alleviated by oxytocin administration. Furthermore, IF staining of PV co-localization with vesicular glutamate transporter 1 or vesicular GABA transporter indicated a balanced excitation/inhibition effect of neurotransmitters on PV interneurons after oxytocin administration in the SAE mice, leading to an improved cognitive function. In conclusion, oxytocin treatment improved cognitive function by increasing the number of PV+ neurons in the hippocampal CA1 region, restoring the balance of excitatory/inhibitory synaptic transmission on PV interneurons, and enhancing hippocampal CA1 local field potential gamma oscillations. These findings suggest a potential mechanism underlying the beneficial effects of oxytocin in SAE.

Systemic inflammation may induce sepsis-associated encephalopathy (SAE), a common condition among sepsis patients that was first reported in 1827[1]. SAE is a prevalent cerebral disorder frequently observed in intensive care units, and its main symptoms are acute, diffuse cognitive dysfunction and altered levels of consciousness level[2]. Neuroinflammation, altered neurotransmission, and abnormal cerebral metabolism have been implicated in the pathogenesis of dysfunction and potentially contribute to the development of SAE[3]. However, the complex mechanisms underlying the development of SAE remain uncertain and still need to be elucidated.

In the hippocampus, inhibitory parvalbumin (PV) interneurons play a crucial role in facilitating complex cognitive processes, particularly for those related to learning and memory. It has been demonstrated that impaired excitation and inhibition of PV interneurons may contribute to cognitive impairments[4]. Gamma oscillations are fundamental and prominent frequency band detected in human electroencephalograms. The synchronous electrical activity of the gamma band originates from the interaction between excitatory pyramidal neurons and inhibitory PV+ neurons accompanied by synchronous inhibitory postsynaptic membrane potentials[5]. These gamma oscillations play a crucial role in working memory and are fundamental elements of higher cognitive function and sensory processing[5–6]. Synchronization increases during the formation stages of learning and memory[7]. For example, Alzheimer's disease interferes with hippocampal gamma oscillation and long-term potentiation, which are recognized as fundamental processes for learning and memory[8]. In mouse models of SAE, cognitive impairments have been associated with a decreased expression of PV[9] and alterations in gamma oscillations[10]. The decreased gamma oscillations in the cornu ammonis 1 (CA1) region of the hippocampus may be one possible cause of SAE[4]. However, the established methodologies that effectively target the excitation of PV+ neurons and gamma oscillations to mitigate cognitive dysfunction are currently lacking.

Mounting evidence indicates that oxytocin is involved in the processes of learning and memory[11], including in SAE[12]. Oxytocin plays a role in regulating the maturation of excitatory neurons in the hippocampus and maintaining the balance between physiological excitation and inhibition. Disruption of this balance may lead to neurobehavioral disorders[13–14]. Oxytocin has a selective stimulatory effect on a specific class of inhibitory interneurons within the CA1 region of the hippocampus[15]; it also has an indirect inhibitory regulatory effect on the excitability of pyramidal neurons[16–17]. Specifically, oxytocin promotes the synaptic-mediated inhibition of CA1 pyramidal neurons by increasing the firing rate of gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA)-ergic interneurons located in the pyramidal cell layer[18]. Nonetheless, it is unclear whether exposure to oxytocin modulates the balance between excitatory and inhibitory influences on PV+ fast-spiking interneurons. It also remains uncertain whether gamma oscillation and cognitive dysfunction can be restored in the SAE mice.

In the current study, we aimed to investigate the therapeutic effects of oxytocin on cognitive dysfunction in SAE mice induced by lipopolysaccharide (LPS). LPS was administered intraperitoneally to induce systemic inflammation, while oxytocin was delivered intranasally. We performed behavioral assessments to evaluate cognitive variations and employed Golgi staining to analyze changes in hippocampal synaptic structure. A linear silicon probe was inserted into the CA1 region of the right hippocampus of each mouse to evaluate gamma oscillatory activity and to record local field potential (LFP). We also quantified the expression of vesicular glutamate transporter 1 (VGluT1) and vesicular GABA transporter (VGAT) on PV+ neurons in the CA1 hippocampal region by immunofluorescence (IF) staining, which allowed us to explore the underlying mechanisms of oxytocin's effects on PV interventions and cognitive dysfunction in the SAE mice.

Sixty healthy male C57BL/6 mice (6–8 weeks old) obtained from Gempharmatech Co., Ltd. (Nanjing, Jiangsu, China) were housed in groups (2–4 per cage) at the Animal Center of Jinling Hospital, Nanjing, China. A constant temperature of 22–23 ℃ was maintained under a 12-h light/dark cycle in the cages. Ad libitum food and water were available to all mice. Experiments were initiated after a 7-day acclimation period. Male mice were used in the experiments to exclude behavioral effects of estrogen or endogenous oxytocin.

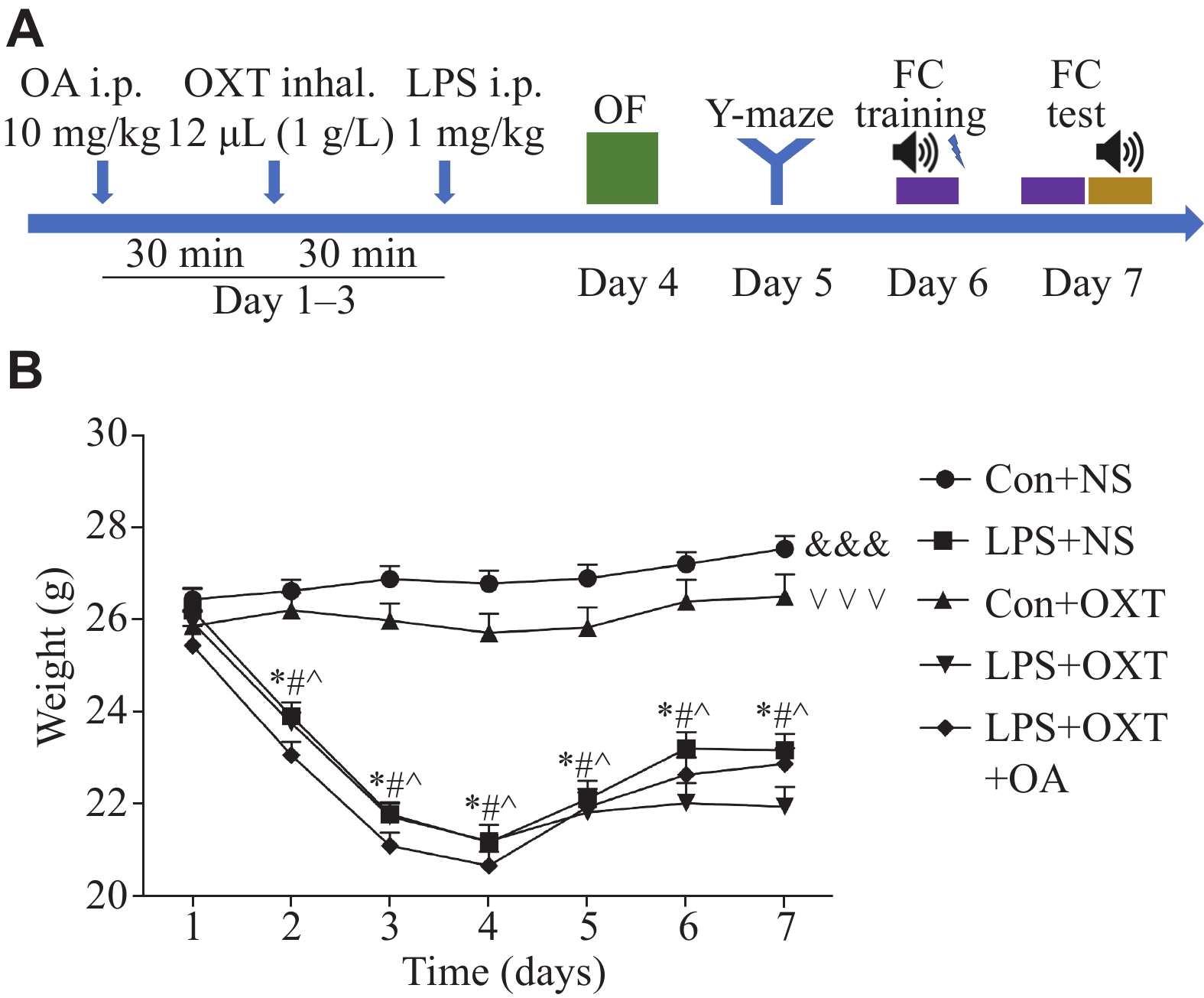

A concise flow chart of the experimental process is shown in Fig. 1A. Intraperitoneal (i.p.) injections of LPS (1 mg/kg body weight; Cat. #L4130, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) were administered to the mice daily from day 1 to day 3. A total of 12 μL of oxytocin (1 g/L; Cat. #HY-17571A/CS-3775, MedChemExpress, Monmouth Junction, NJ, USA) was administered via inhalation into each nasal cavity 30 min before the LPS treatment from day 1 to day 3. A selective oxytocin receptor (OXTR) antagonist (OA) (Cat. #HY-15008, MedChemExpress), dissolved in saline (5 g/L), was administered at a dose of 10 mg/kg body weight 30 min before the oxytocin treatment from day 1 to day 3. The control mice received the same amount of saline.

Every behavioral test was conducted in a darkened and quiet room between 9:00 a.m. and 5:00 p.m. The mice were acclimated to the test chambers 60 min before the test. Experimental grouping was blinded to the investigators during the tests.

Each mouse was placed in a cube box (XR-XZ301, Shanghai Xinruan Information Technology Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) to explore freely for 5 min to assess behaviors related to anxiety and motor ability. The open field test was carried out in a 40 cm × 40 cm × 40 cm box. The bottom plate and four walls were all white, and the bottom plate was evenly divided into 4 × 4 small cells horizontally and vertically. The 6th, 7th, 10th, and 11th small cells were defined as the central cells, ordered from the top to the bottom and the left to the right. The test was conducted in a quiet environment (the experimenter observed from a distance, and there was no movement or sound during the test). The light level in the box was set to a low level (approximately 30 lux). After being placed gently in the center of the box, each mouse was free to explore for 5 min, and the movement of each mouse was recorded and analyzed during the test. After each test, the inner wall and bottom of the box were wiped with alcohol gauze to ensure that the experimental results of the next mouse were not affected by residual information (size, urine, odor, etc.).

Each mouse was placed in the Y-maze (XR-XY1032, Shanghai Xinruan Information Technology Co., Ltd.) to explore freely for 8 min to evaluate motor ability and working memory. The Y-maze was constructed in a 35 cm × 5 cm × 15 cm (length × width × height) apparatus. The maze consisted of three identical arms (A, B, and C), and the angle between each pair of arms was 120°. On day 4, to evaluate spatial working memory, each mouse was placed at the far end of the same arm and allowed to explore freely for 8 min. The arm sequence of arm entries was recorded. A thorough cleaning of the apparatus was conducted after each trial using 75% ethanol. It was called the spontaneous alternation performance, if the mouse entered at least three different arms. The spontaneous alternation percentage was calculated following the formula: (number of alternating triads)/(total number of arm entries − 2) × 100%.

To assess the hippocampal-dependent memory, each mouse was placed in the chamber (XR-XC404, Shanghai Xinruan Information Technology Co., Ltd.) for 5 min without any tone or foot shock to test their contextual fear conditioning. On day 5, the mice were individually placed in a chamber measuring 30 cm × 30 cm × 45 cm (length × width × height) for training. On day 6, the mice were tested to assess their associative memory. During training, each mouse was allowed to explore freely for 3 min. This was followed by a 30 s tone (70 dB,

A linear silicon probe was planted in the CA1 region of the right hippocampus of each mouse, and then LFP was used to obtain the gamma band power. After anesthetization with an i.p. administration of pentobarbital sodium (40 mg/kg body weight), an apparatus with left and right ear rods was used to fix each mouse. The bregma and posterior fontanelle were exposed after the cranial crest was cut along the longitudinal incision of each mouse. A 16-channel linear silicon probe was planted in the CA1 region of the right hippocampus after craniotomy and removal of the dura mater. According to the brain atlas of the mouse, stereotaxic coordinates were determined (posterior, 2.2 mm; lateral, 1.5 mm; and depth, 1.6 mm). During the indicated time points, the LFPs of mice were recorded in home cages with the OmniPlex recording system (Hong Kong Plexon Co., Ltd., Hong Kong, China). After being filtered at 0.3–300 Hz, 2 kHz was selected for amplifying and digitizing the LFP signals. The powerline artifact was removed using a 50-Hz notching filter. The wideband recordings were down-sampled at

In the CA1 hippocampal region, the expression of PV+ neurons, the co-expression of OXTR with PV+ or CaMKⅡ+ neurons, and the co-expression of PV+ neurons with vesicular glutamate transporter 1 (VGluT1) or vesicular GABA transporter (VGAT) were detected by IF staining. Following behavioral tests on day 7, the mice were deeply anesthetized and then perfused transcardially with cold saline followed by paraformaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline. After harvesting, the brain tissues were processed with a series of ethanol and xylene washes for dehydration and clearing. The tissue blocks were then immersed in paraffin and rolled in the groove to ensure that all sides of the tissue blocks were uniformly contacted with the paraffin liquid. All tissues were preserved for slicing, sectioned into 8-μm-thick slices, and carefully placed on glass slides. The slides underwent a series of treatments, including immersions in xylene and ethanol, and antigen retrieval in EDTA buffer. During the above process, the drying of slices because of the excessive evaporation of buffer solution was avoided. After thorough washing, the sections were circled and sequentially incubated with primary and secondary antibodies before DAPI staining and mounting. All slides were visualized with a microscope (Scope A1, ZEISS, Germany).

To ensure the electrode was placed in the hippocampus CA1 area with the method described above, the probe was dipped in the red fluorescence probe solution (Dil, 10 μmol/L; Cat. #C1036, Beyotime, Shanghai, China) before being implanted in the brain. The electrode was extracted gently after implantation was completed, and the hippocampus was sliced for IF staining to check if the electrode position was accurate.

The following primary antibodies were used: mouse monoclonal anti-VGluT1 (1∶

Golgi staining was performed to test the hippocampal synaptic structure changes in each group. A Golgi Stain Kit (#PK401, FD Neuro Technologies, Columbia, MD, USA) was used for Golgi staining. The experiment was conducted following the manufacturer's instructions. The neurons and dendritic spines were captured with the microscope (Scope A1, ZEISS) under 200× and oil-immersion

Data were presented as mean ± standard deviation. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS (edition 25; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). The mean values between groups were compared by repeated-measurement ANOVA or two-way ANOVA. For pairwise comparisons among multiple groups, the Bonferroni method was used. Statistical significance was indicated by P < 0.05.

First, we investigated the effects of LPS on the mortality and weight of the mice. No animal died in any group. As shown in Fig. 1B, body weight fluctuated after the LPS challenge. In comparison to day 1, the body weight in the LPS + normal saline (NS) group, LPS + oxytocin (OXT) group, and LPS + OXT + OA group was significantly lower on days 2 to 7 (all P-values < 0.05). Overall significant differences (all P-values <

No significant differences were observed in the total distance moved (P = 0.61) or time spent in the central area (P = 0.62) among the groups during the open field test (Fig. 2A and 2B). The results indicate that LPS-challenge as well as all the other treatments do not affect motor ability or anxiety-like behavior of the mice.

The spontaneous alteration percentage was significantly lower (P <

In contextual fear conditioning tests, the freezing response percentage of mice was significantly lower (P <

In cued fear conditioning tests, we observed no significant difference in the freezing response percentage among the groups (P =

The results of Golgi staining showed a significant decrease in the density of the dendritic spines in the LPS + NS group, compared with the Con + NS group (P <

LFP was used to assess the gamma band power. Gamma band waves at different frequencies were filtered from original LFP in the CA1 hippocampal region (Fig. 4A). The example PSD of LFP heat map (Fig. 4B) and the PSDs of LFP in the CA1 hippocampal region (Fig. 4C) among the groups were derived. The PSD of the slow gamma band in the LPS + NS group was significantly decreased (P <

As shown in Fig. 5A and 5B, the density of PV+ cells in the CA1 hippocampal region was significantly decreased (P =

As shown in Fig. 5C and 5D, the expression of OXTR on PV+ neurons in the CA1 hippocampal region was significantly increased (P =

As shown in Fig. 5E and 5F, no significant differences (P > 0.05) were observed among the groups of mice. This indicates that the LPS challenge as well as all the other treatments do not impair the expression of OXTR on the excitatory neurons in the CA1 hippocampal region of the mice.

As shown in Fig. 6, compared with the Con + NS group, the co-localization of PV with VGluT1 was decreased significantly (P =

In the current study, we established an SAE model by intraperitoneal injection of LPS and investigated the therapeutic effect of intranasal administration of oxytocin on SAE and its potential mechanisms. We observed that post-sepsis oxytocin inhalation alleviated cognitive dysfunction and behavioral changes in cognitive function in the SAE mice. The changes in LFP and gamma oscillations in the hippocampal CA1 area of the mice were involved in this process. Furthermore, alterations in the excitatory and inhibitory neurotransmitters acting on PV interneurons may be the underlying mechanisms. Therefore, oxytocin inhalation provides a new perspective for targeted interventions in SAE.

Systemic inflammation induces encephalopathy, and its underlying mechanisms are multi-faceted and complex[3]. Intraperitoneal injection of LPS is a commonly used method for establishing SAE models. In our study, a single intraperitoneal injection of LPS at a dosage of 1 mg/kg for three consecutive days caused systemic inflammation and damage to the blood-brain barrier in mice, ultimately resulting in SAE[19]. Behavioral tests confirmed the successful establishment of a stable and reliable SAE animal model. The current study aimed to investigate the LPS-induced encephalopathy in the hippocampal CA1 region, which plays a pivotal role in cognitive function modulation through its connections from the dentate gyrus (DG) to the CA3 and subsequently to the CA1[20–23]. Furthermore, the CA1 region is known to be more vulnerable to oxidative stress, apoptosis, and ischemia, compared with the DG and CA3 regions[24–27].

Intranasally delivered oxytocin may quickly reach the brain and take effect, as it bypasses the first-pass metabolism and the blood-brain barrier. Compared with intraperitoneal injection, intranasal oxytocin administration significantly increased oxytocin concentration in the dorsal hippocampus within the first 30 min, maintaining elevated levels for several hours[28]. In addition, oxytocin has also been reported to act on the hippocampus to improve cognitive dysfunction[11–12]. Furthermore, oxytocin regulates the development of excitatory neurons in the hippocampus and contributes to maintaining a physiological excitatory/inhibitory balance, the disruption of which may lead to neurobehavioral disorders[13]. In the current study, we demonstrated that oxytocin treatment upregulated PV expression and enhanced gamma oscillations, thereby improving cognitive function in SAE mice.

In recent years, numerous studies have indicated an association between the diminished PV expression levels and disrupted gamma oscillation patterns with cognitive impairments[29–30]. Normal cerebral function relies on the dynamic balance between excitatory and inhibitory neurons. The synchronized electrical activities of excitatory and inhibitory neurons form the basis of gamma-band synchronous electrical activity[5], which are crucial for spatial working memory[31]. Gamma rhythms also recruit neurons and glial responses to mitigate pathological changes associated with Alzheimer's disease[6,32] and improve cognition[33]. Fast-spiking PV interneurons are a type of inhibitory GABA-ergic neuron and their synchronous electrical activities are important for maintaining the excitation/inhibition dynamic balance; moreover, the fast-spiking PV interneurons are correlated with gamma oscillations[8,34]. In the current study, we observed alterations in gamma oscillations of LFPs in the hippocampal CA1 region, prompting us to further investigate the function of gamma-related PV+ neurons and the mechanisms underlying their altered excitability alterations in SAE.

Importantly, glutamate acts as an excitatory neurotransmitter, while GABA acts as an inhibitory neurotransmitter within the central nervous system[35–36]. In the current study, we chose and quantified the presynaptic markers of both excitatory and inhibitory neurons, namely, VGluT1 and VGAT. VGluT1 is located in the vesicles of the excitatory synapses, while VGAT is located in the vesicles of the inhibitory synapses[37]. These transporters significantly contribute to the regulation of excitation/inhibition neurotransmission by influencing vesicle filling and quantum size[38]. Based on the quantified levels, it can be inferred that imbalanced bidirectional effects on PV interneurons are derived from the enhanced inhibitory VGAT neurotransmissions and the declined excitatory VGLUT1 neurotransmissions in the LPS-challenged mice. These effects may mediate the excitation/inhibition imbalance of PV interneurons at the synaptic level. In contrast, oxytocin alleviated excitation/inhibition imbalance by enhancing the VGluT1 effects on PV, while decreasing the VGAT effects.

However, the current study also has some limitations. Firstly, it has been reported that LPS administration causes splenomegaly and elevates levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines in the blood, with positive correlations between spleen weight and cytokine levels in the blood[39–40]. However, it was not measured whether oxytocin attenuated splenomegaly or systemic inflammation in the LPS-treated mice in the current study. Mice mortality did not occur in any group in the current study. However, the mortality may reach 70% in SAE patients in intensive care units[3]. In the current study, cerebral dysfunction was derived from a relatively low level of inflammation, and it was easy to investigate the effect of oxytocin on cerebral function without dealing with other confounding factors. Secondly, the balance of excitation and inhibition of the brain is controlled by a variety of neurons, and the inhibitory PV interneurons are GABA-ergic neurons that account for 40%–50% of all GABA-ergic neurons in the brain. Although inhibitory interneurons account for a small proportion of total brain neurons, most of which are excitatory pyramidal neurons, the neural circuits are in a state of balance between synaptic excitation and inhibition; this balance is usually based on fast glutamate and slow GABA inputs, and inhibition is two to six times stronger than excitation[41]. Gamma oscillation is a basic form of synchronous electrical activity in the nerve micro-loop, which plays an important role in maintaining cognitive function. PV interneurons have the characteristics of fast discharge and are the main force producing gamma oscillation[42]. It is impossible to study the effects of all excitatory and inhibitory neurons at one time. Therefore, we have chosen to study the gamma oscillation that plays a significant role in neural function. In gamma oscillations, the change in slope at the specific slow gamma frequency corresponds to the alterations in excitation/inhibition balance[43]. Therefore, in the current study, the frequency band of slow gamma oscillations was selected to investigate the PSD change in the LPS-challenged mice. Finally, OXTR is expressed in several interneurons, such as somatostatin (SST), PV, and pyramidal neurons[44], and some interneurons, such as SST cells, may be specifically activated by OXTR[45]. Furthermore, SST neurons inhibit PV neurons and also receive excitation inputs from pyramidal cells[46–47]. In the current study, only PV interneurons and the related gamma oscillations were investigated, and it remains unknown whether other interneurons activated by OXTR are involved in the process of SAE. We found that the expression of PV decreased, and that the co-localization of VGluT1 and VGAT on PV+ neurons decreased, indicating changes in neurotransmitters acting on the postsynaptic membrane. However, it remains unclear whether the synapses are decreased. Consequently, it needs to be demonstrated by measuring PSD95, GAD67, and Gephyrin.

It has been reported that OXTR is distributed in both the cerebral cortex and hippocampus[48]. In the central nervous system, oxytocin inhibited inflammation of microglial cells and attenuated the activation of microglial cells in the LPS-treated mice[49]. Consistent with a recent study, the LPS-challenged mice showed higher levels of OXTR on PV+ neurons in the CA1 hippocampal region in the current study[12]. The increased OXTR expression in the brain may play a role in cerebral anti-inflammation. However, further studies are needed to elucidate the mechanisms underlying the activation or inhibition of VGluT1 and VGAT on PV+ neurons.

In conclusion, the results of the current study indicate that oxytocin administration improves cognitive function in the SAE mice, possibly by stabilizing the excitation/inhibition balance of PV+ fast-spiking interneurons and enhancing gamma oscillations (Fig. 7). The stabilization of PV interneuron activity and the enhancement of gamma oscillations may play a key role in mitigating behavioral and cognitive impairments in LPS exposure-induced SAE. Together, our findings contribute to a better understanding of behavioral and cognitive impairments in the SAE mice and provide potential targets for exploring effective treatments. However, more specific or comprehensive studies based on advanced methods including optogenetic and pharmacological methods are needed to validate our results.

None.

This work was supported by grants from the general project of Nanjing Medical University Science and Technology Development Foundation (Grant No. NMUB20210112).

CLC number: R747.9, Document code: A

The authors reported no conflict of interests.

| [1] |

Bleck TP. Sepsis on the brain[J]. Crit Care Med, 2002, 30(5): 1176–1177. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200205000-00047

|

| [2] |

Jeppsson B, Freund HR, Gimmon Z, et al. Blood-brain barrier derangement in sepsis: cause of septic encephalopathy?[J]. Am J Surg, 1981, 141(1): 136–142. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(81)90026-X

|

| [3] |

Cotena S, Piazza O. Sepsis-associated encephalopathy[J]. Transl Med UniSa, 2012, 2: 20–27.

|

| [4] |

Wu X, Ji M, Yin X, et al. Reduced inhibition underlies early life LPS exposure induced-cognitive impairment: Prevention by environmental enrichment[J]. Int Immunopharmacol, 2022, 108: 108724. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2022.108724

|

| [5] |

Lepousez G, Lledo PM. Odor discrimination requires proper olfactory fast oscillations in awake mice[J]. Neuron, 2013, 80(4): 1010–1024. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.07.025

|

| [6] |

Iaccarino HF, Singer AC, Martorell AJ, et al. Gamma frequency entrainment attenuates amyloid load and modifies microglia[J]. Nature, 2016, 540(7632): 230–235. doi: 10.1038/nature20587

|

| [7] |

Heusser AC, Poeppel D, Ezzyat Y, et al. Episodic sequence memory is supported by a theta-gamma phase code[J]. Nat Neurosci, 2016, 19(10): 1374–1380. doi: 10.1038/nn.4374

|

| [8] |

Park K, Lee J, Jang HJ, et al. Optogenetic activation of parvalbumin and somatostatin interneurons selectively restores theta-nested gamma oscillations and oscillation-induced spike timing-dependent long-term potentiation impaired by amyloid β oligomers[J]. BMC Biol, 2020, 18(1): 7. doi: 10.1186/s12915-019-0732-7

|

| [9] |

Ji M, Qiu L, Tang H, et al. Sepsis-induced selective parvalbumin interneuron phenotype loss and cognitive impairments may be mediated by NADPH oxidase 2 activation in mice[J]. J Neuroinflammation, 2015, 12(1): 182. doi: 10.1186/s12974-015-0401-x

|

| [10] |

Gao R, Ji M, Gao D, et al. Neuroinflammation-induced downregulation of hippocampacal neuregulin 1-ErbB4 signaling in the parvalbumin interneurons might contribute to cognitive impairment in a mouse model of sepsis-associated encephalopathy[J]. Inflammation, 2017, 40(2): 387–400. doi: 10.1007/s10753-016-0484-2

|

| [11] |

Ye C, Cheng M, Ma L, et al. Oxytocin nanogels inhibit innate inflammatory response for early intervention in Alzheimer's disease[J]. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces, 2022, 14(19): 21822–21835. doi: 10.1021/acsami.2c00007

|

| [12] |

Jiang J, Zou Y, Xie C, et al. Oxytocin alleviates cognitive and memory impairments by decreasing hippocampal microglial activation and synaptic defects via OXTR/ERK/STAT3 pathway in a mouse model of sepsis-associated encephalopathy[J]. Brain Behav Immun, 2023, 114: 195–213. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2023.08.023

|

| [13] |

Ripamonti S, Ambrozkiewicz MC, Guzzi F, et al. Transient oxytocin signaling primes the development and function of excitatory hippocampal neurons[J]. eLife, 2017, 6: e22466. doi: 10.7554/eLife.22466

|

| [14] |

Owen SF, Tuncdemir SN, Bader PL, et al. Oxytocin enhances hippocampal spike transmission by modulating fast-spiking interneurons[J]. Nature, 2013, 500(7463): 458–462. doi: 10.1038/nature12330

|

| [15] |

Crane JW, Holmes NM, Fam J, et al. Oxytocin increases inhibitory synaptic transmission and blocks development of long-term potentiation in the lateral amygdala[J]. J Neurophysiol, 2020, 123(2): 587–599. doi: 10.1152/jn.00571.2019

|

| [16] |

Mühlethaler M, Charpak S, Dreifuss JJ. Contrasting effects of neurohypophysial peptides on pyramidal and non-pyramidal neurones in the rat hippocampus[J]. Brain Res, 1984, 308(1): 97–107. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(84)90921-1

|

| [17] |

Tiberiis BE, McLennan H, Wilson N. Neurohypophysial peptides and the hippocampus. II. Excitation of rat hippocampal neurones by oxytocin and vasopressin applied in vitro[J]. Neuropeptides, 1983, 4(1): 73–86. doi: 10.1016/0143-4179(83)90011-2

|

| [18] |

Zaninetti M, Raggenbass M. Oxytocin receptor agonists enhance inhibitory synaptic transmission in the rat hippocampus by activating interneurons in stratum pyramidale[J]. Eur J Neurosci, 2000, 12(11): 3975–3984. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2000.00290.x

|

| [19] |

Zhou T, Zhao L, Zhan R, et al. Blood-brain barrier dysfunction in mice induced by lipopolysaccharide is attenuated by dapsone[J]. Biochem Biophys Res Commun, 2014, 453(3): 419–424. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2014.09.093

|

| [20] |

Keinath AT, Nieto-Posadas A, Robinson JC, et al. DG-CA3 circuitry mediates hippocampal representations of latent information[J]. Nat Commun, 2020, 11(1): 3026. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-16825-1

|

| [21] |

Alkadhi KA. Cellular and molecular differences between area CA1 and the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus[J]. Mol Neurobiol, 2019, 56(9): 6566–6580. doi: 10.1007/s12035-019-1541-2

|

| [22] |

Kohara K, Pignatelli M, Rivest AJ, et al. Cell type-specific genetic and optogenetic tools reveal hippocampal CA2 circuits[J]. Nat Neurosci, 2014, 17(2): 269–279. doi: 10.1038/nn.3614

|

| [23] |

Hainmueller T, Bartos M. Parallel emergence of stable and dynamic memory engrams in the hippocampus[J]. Nature, 2018, 558(7709): 292–296. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0191-2

|

| [24] |

Uchino S, Nakamura T, Nakamura K, et al. Real-time, two-dimensional visualization of ischaemia-induced glutamate release from hippocampal slices[J]. Eur J Neurosci, 2001, 13(4): 670–678. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2001.01430.x

|

| [25] |

Wang X, Pal R, Chen X, et al. Genome-wide transcriptome profiling of region-specific vulnerability to oxidative stress in the hippocampus[J]. Genomics, 2007, 90(2): 201–212. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2007.03.007

|

| [26] |

Uysal N, Tugyan K, Aksu I, et al. Age-related changes in apoptosis in rat hippocampus induced by oxidative stress[J]. Biotech Histochem, 2012, 87(2): 98–104. doi: 10.3109/10520295.2011.556665

|

| [27] |

Olufunmilayo EO, Gerke-Duncan MB, Holsinger RMD. Oxidative stress and antioxidants in neurodegenerative disorders[J]. Antioxidants (Basel), 2023, 12(2): 517. doi: 10.3390/antiox12020517

|

| [28] |

Smith AS, Korgan AC, Young WS. Oxytocin delivered nasally or intraperitoneally reaches the brain and plasma of normal and oxytocin knockout mice[J]. Pharmacol Res, 2019, 146: 104324. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2019.104324

|

| [29] |

Ji M, Lei L, Gao D, et al. Neural network disturbance in the medial prefrontal cortex might contribute to cognitive impairments induced by neuroinflammation[J]. Brain Behav Immun, 2020, 89: 133–144. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.06.001

|

| [30] |

Gao Y, Wu X, Zhou Z, et al. Dysfunction of NRG1/ErbB4 signaling in the hippocampus might mediate long-term memory decline after systemic inflammation[J]. Mol Neurobiol, 2023, 60(6): 3210–3226. doi: 10.1007/s12035-023-03278-y

|

| [31] |

Yamamoto J, Suh J, Takeuchi D, et al. Successful execution of working memory linked to synchronized high-frequency gamma oscillations[J]. Cell, 2014, 157(4): 845–857. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.04.009

|

| [32] |

Verret L, Mann EO, Hang GB, et al. Inhibitory interneuron deficit links altered network activity and cognitive dysfunction in Alzheimer model[J]. Cell, 2012, 149(3): 708–721. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.02.046

|

| [33] |

Martorell AJ, Paulson AL, Suk HJ, et al. Multi-sensory Gamma stimulation ameliorates Alzheimer's-associated pathology and improves cognition[J]. Cell, 2019, 177(2): 256–271. e22. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2019.02.014

|

| [34] |

Chen G, Zhang Y, Li X, et al. Distinct inhibitory circuits orchestrate cortical beta and gamma band oscillations[J]. Neuron, 2017, 96(6): 1403–1418. e6. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2017.11.033

|

| [35] |

Conti F, Weinberg RJ. Shaping excitation at glutamatergic synapses[J]. Trends Neurosci, 1999, 22(10): 451–458. doi: 10.1016/S0166-2236(99)01445-9

|

| [36] |

Cherubini E, Conti F. Generating diversity at GAB Aergic synapses[J]. Trends Neurosci, 2001, 24(3): 155–162. doi: 10.1016/S0166-2236(00)01724-0

|

| [37] |

Eiden LE. The vesicular neurotransmitter transporters: current perspectives and future prospects[J]. FASEB J, 2000, 14(15): 2396–2400. doi: 10.1096/fj.00-0817rev

|

| [38] |

Wilson NR, Kang J, Hueske EV, et al. Presynaptic regulation of quantal size by the vesicular glutamate transporter VGLUT1[J]. J Neurosci, 2005, 25(26): 6221–6234. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3003-04.2005

|

| [39] |

Zhang J, Ma L, Chang L, et al. A key role of the subdiaphragmatic vagus nerve in the depression-like phenotype and abnormal composition of gut microbiota in mice after lipopolysaccharide administration[J]. Transl Psychiatry, 2020, 10(1): 186. doi: 10.1038/s41398-020-00878-3

|

| [40] |

Zhang J, Ma L, Wan X, et al. (R)-Ketamine attenuates LPS-induced endotoxin-derived delirium through inhibition of neuroinflammation[J]. Psychopharmacology (Berl), 2021, 238(10): 2743–2753. doi: 10.1007/s00213-021-05889-6

|

| [41] |

Xue M, Atallah BV, Scanziani M. Equalizing excitation-inhibition ratios across visual cortical neurons[J]. Nature, 2014, 511(7511): 596–600. doi: 10.1038/nature13321

|

| [42] |

Bartos M, Vida I, Jonas P. Synaptic mechanisms of synchronized gamma oscillations in inhibitory interneuron networks[J]. Nat Rev Neurosci, 2007, 8(1): 45–56. doi: 10.1038/nrn2044

|

| [43] |

Gao R, Peterson EJ, Voytek B. Inferring synaptic excitation/inhibition balance from field potentials[J]. Neuroimage, 2017, 158: 70–78. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2017.06.078

|

| [44] |

Young WS, Song J. Characterization of oxytocin receptor expression within various neuronal populations of the mouse dorsal hippocampus[J]. Front Mol Neurosci, 2020, 13: 40. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2020.00040

|

| [45] |

Maldonado PP, Nuno-Perez A, Kirchner JH, et al. Oxytocin shapes spontaneous activity patterns in the developing visual cortex by activating somatostatin interneurons[J]. Curr Biol, 2021, 31(2): 322–333. e5. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2020.10.028

|

| [46] |

Udakis M, Pedrosa V, Chamberlain SEL, et al. Interneuron-specific plasticity at parvalbumin and somatostatin inhibitory synapses onto CA1 pyramidal neurons shapes hippocampal output[J]. Nat Commun, 2020, 11(1): 4395. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-18074-8

|

| [47] |

Magnin E, Francavilla R, Amalyan S, et al. Input-specific synaptic location and function of the α5 GABAA receptor subunit in the mouse CA1 hippocampal neurons[J]. J Neurosci, 2019, 39(5): 788–801. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0567-18.2018

|

| [48] |

Carter CS, Kenkel WM, MacLean EL, et al. Is oxytocin "nature's medicine"?[J]. Pharmacol Rev, 2020, 72(4): 829–861. doi: 10.1124/pr.120.019398

|

| [49] |

Yuan L, Liu S, Bai X, et al. Oxytocin inhibits lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammation in microglial cells and attenuates microglial activation in lipopolysaccharide-treated mice[J]. J Neuroinflammation, 2016, 13(1): 77. doi: 10.1186/s12974-016-0541-7

|